What the Tacoma officer acquittals could mean for future police trials

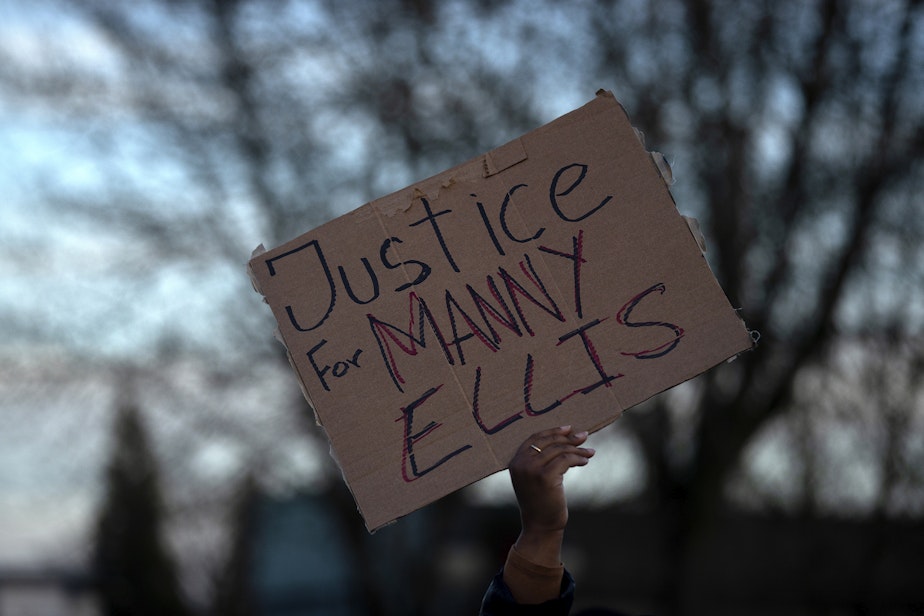

This week, a jury in Pierce County Superior Court found three officers not guilty of the 2020 death of Manuel (Manny) Ellis, a Black man, in their custody.

Ellis, 33, died during an encounter with Tacoma police during which he was handcuffed, hogtied, and had a spit hood placed over his head. He told officers he could not breathe while being restrained. The medical examiner concluded his death was a homicide.

The officers' defense team argued that Ellis' death was the result of a heart condition and the methamphetamine found in his system.

KUOW followed up on the case with two legal experts to assess how it played out in court, what was behind the verdict, and what it means moving forward.

- Deborah Ahrens is a professor at Seattle University School of Law, where she is also vice dean for intellectual life. She previously worked for the ACLU and as a state public defender in Richland County, South Carolina.

- David Owens is an assistant professor at the University of Washington Law School, and is a full-time civil rights attorney. He previously represented the family of Isaiah Obet, who was killed by an Auburn police officer in 2017, and the family of Mi'Chance Dunlap-Gittens who was killed by King County sheriff deputies in Burien in 2017.

Decisions that influenced the trial

Both lawyers pointed to how decisions around what was allowed in court influenced the trial. In short, Manny Ellis' history was allowed as evidence while the police officers' history was not.

“I think that there were some rulings pre-trial … like the history of one of the police officers at the police academy that had raised some antenna about whether or not he was using force in situations where he shouldn't," Ahrens said. "The trial court kept that information from the jury; the jury probably would have liked to have that information. It might have caused them to view their stories differently.”

Owens said that the jury was able to hear about Ellis' past encounters with police, and drug use.

“I was shocked to hear in the opening arguments, and then it was part of the case itself, the idea that the officers were permitted to introduce information about Manny Ellis' alleged prior contacts with police officers, alleged prior drug use, things like that. In the law, we call this 'propensity evidence'.

“That evidence itself is about Manny Ellis using drugs at a prior time, and this is a big structural bias that injured the trial … when Black men are accused of or believed to have done drugs, that is associated with dangerousness, that is associated with harm, that is associated with being a threat — just that allegation itself. So if you think about your students at the University of Washington in the Greek system, partying and doing drugs, nobody automatically associates that with a threat.”

Rather, Owens said, there are studies that indicate drug use often prompts a perception of threat from Black men. That is why this aspect of the case “shocked” him.

'Excited delirium'

The concept of "excited delirium" was brought up in court. Excited delirium is associated with drug use and is purportedly characterized by a person becoming agitated and distressed before dying.

“Which is fake. It is not real," Owens argued. "It is something that the police have made up … it is something that has been derived and made up from sort of 'police junk science sources' to justify and to sort of excuse in-custody deaths, just like this one. And it has very, very racist origins.”

The medical diagnosis of excited delirium has been rejected by multiple medical authorities, most recently by the American College of Emergency Physicians. The state of Colorado also recently nixed the diagnosis from all law enforcement training documents.

“I think that examining and forbidding excited delirium as part of policing should occur," Owens said.

Officers had an advantage other defendants might not

“I think that really, to some extent, what this trial came down to was that the police officers testified; they were able to testify," Aherns said. "These are police officers who were in a better position to testify than your average criminal defendant would be."

Putting police on trial is different than other defendants, she argued. Officers are expected to use force as part of their job, they are well-educated about giving statements to police and investigators, and they often lack criminal histories that could cast doubt on their credibility.

"One or more of the officers had an opportunity to consult with lawyers before they spoke to investigators, which again, is going to make it a lot easier for you to make statements that don't expose you to more criminal liability... That's something that many criminal defendants don't have the luxury of having."

"And when they did testify, they stayed pretty calm. They gave stories that could be believed, and the defense just has to be believable — they don't have to be believed, they just have to persuade the jury that their version of the events could be true. That’s a different burden than the state (has), which has to prove that their version of the events is true. I think that these were people who are much better positioned at a criminal trial than normally you would be."

What about Initiative 940?

The case surrounding the death of Manny Ellis at the hands of Tacoma police officers has been viewed as the first case resulting from the voter-approved Initiative 940. That initiative, among other things, eliminated a long-held legal standard of not charging officers in deadly force cases unless it can be proven they acted with "malice."

Owens never expected major changes from I-940, and instead looks to other "mechanisms" to hold police accountable, such as civil rights lawsuits, administrative reviews, citizen complaints, and democratic procedures.

“All of those things still exist, all of those things are very powerful mechanisms for getting change and for getting reform that we want to see," he said.

“The criminal legal system is a huge behemoth … all these other structural issues weren't going to change it … I understand there's disillusionment, but I want to say there are lots and lots and lots of opportunities that still exist for people in Tacoma, for Washingtonians, for all of us together to try to think about how to prevent something like this from happening in the future.”

Ahrens argued that similar cases could still have different outcomes because of I-940.

“I think, in general, to prosecute police officers, it's a lot easier to post- I-940 than it was prior to that," she said, noting that there were unique factors to the Tacoma police officers' case that allowed it to play out the way it did, such as the use of witness testimony.

“I just think that it's an illustration that it's going to be hard," she said. "But it's not impossible. Prosecutors don't, and aren't supposed to, win every case. And the fact that they lost this one doesn't mean that other prosecutions couldn't be successful.”

“I hope people don't take the acquittal of the police officers as a sign that if you're concerned about police violence, there's nothing to be done about it. Criminal prosecution is just one tool that people have. And for example, there's an initiative ... that has to do with police chases, that looks like it's going to be making its way onto our next ballot. We do have the option to control police force through legislation. There's also civil litigation, better police training. This doesn't have to be a sign that it's simply hopeless to try to deal with police violence.”

KUOW's Jason Pagano and Dyer Oxley contributed to this article.