Missed chemo treatments, water-crossed lovers separated: Washington state's broken ferry system

If a road closes near your home, you can probably find another way around. But if you live on an island, and your boat doesn’t come, you’re probably out of luck.

That’s been happening a lot lately in Washington state, home to the largest ferry system in the country. Almost 19 million people used it last year — and it’s breaking down.

Additional, recently hired crew members are having a positive impact on the system, but it'll be more than a decade before it starts gaining more boats than it's losing.

Bari Willard lives in the San Juan Islands near the border with Canada. She has cancer and needs to get from her home on Orcas Island to another island close by for treatment. So she's waiting in a line of cars with her husband Andy to get on the ferry.

These days, she says it’s often late — or doesn’t come at all.

“There's a lot of — I want to say — anxiety," she says. "If it comes too late, then the chemo will be too late and I'll be too late for the ferry getting back. That's a problem.”

It could mean she can’t pick her daughter up from school. Or her husband might have to shift his hours so he’s working until midnight at his custodian job. And sometimes she has to end her chemo treatments with them half-done and return the next day. That can mean missing another day of work.

1 of 2

Andy and Bari Willard await the ferry that will take her to her chemotherapy on San Juan Island

1 of 2

Andy and Bari Willard await the ferry that will take her to her chemotherapy on San Juan Island

Today, the boat came — and got her there on time.

But the ferry service canceled over 4,000 sailings in 2023. The reason is that a perfect storm of aging ferry boats and crew shortages created a crisis.

The seed was planted about 25 years ago, when an anti-tax initiative resulted in a slashed ferry budget, according to Steve Nevey, the new head of Washington State Ferries.

RELATED: Washington's ferry system has a trust problem

“Since then, the system's just been chronically underfunded,” he says.

That means there wasn’t enough money to hire and train new crew members as older staff retired.

“Then the pandemic accelerated that," Nevey adds. "A lot of people decided, 'I'm retirement eligible and I don't want to deal with this pandemic stuff. So I’m going to retire now and be done.'”

These days, when a crew member calls in sick, an entire ferry run can get canceled.

The money issue affects infrastructure too, Nevey adds.

“We haven't had funding to be able to build new boats at the pace we need to be building new boats.”

RELATED: Could a broken WA ferry system help cities grow more sustainably?

When aging boats break down, that leads to huge delays.

1 of 2

A ferry seen from Orcas Island, Washington.

1 of 2

A ferry seen from Orcas Island, Washington.

In waterfront cities like Seattle, Bremerton, and Everett, people still have the option of driving the long way around the Puget Sound, which can add 100 miles to someone’s commute. But in that’s not possible in the San Juan Islands — they can’t be reached from the mainland by roads.

Hear more about ferries — and some surprising solutions — on KUOW's economics podcast, Booming.

For Rancher Lori Ann David, an unreliable ferry system means she can’t get her pigs to slaughter.

“You get a bunch of animals in a pen ready for harvest and then there's no ferry to bring the truck over,” she says.

Teachers and students like mother-daughter duo Tenar and Cathy Hall get stranded after school —and have to find a "parent boat," a privately owned boat operated by someone in the community.

For grocery store clerk Ryhien Fielder's part, he can’t get to his husband in Canada.

“We have a long-distance relationship that became a lot longer distance,” he says.

San Juan County’s public defender Alex Frix says sometimes, ferry delays mean a juror from another island can’t make it to trial.

“If enough of your jurors were not from San Juan Island, then you would have the problem of potentially having to declare a mistrial.”

Recently, the Washington State Legislature authorized a ferry crew-hiring spree, which seems to be helping. During the slow winter months of this year, canceled sailings were down 60% compared to last summer.

But when it comes to the aging ferry infrastructure, there's more complexity.

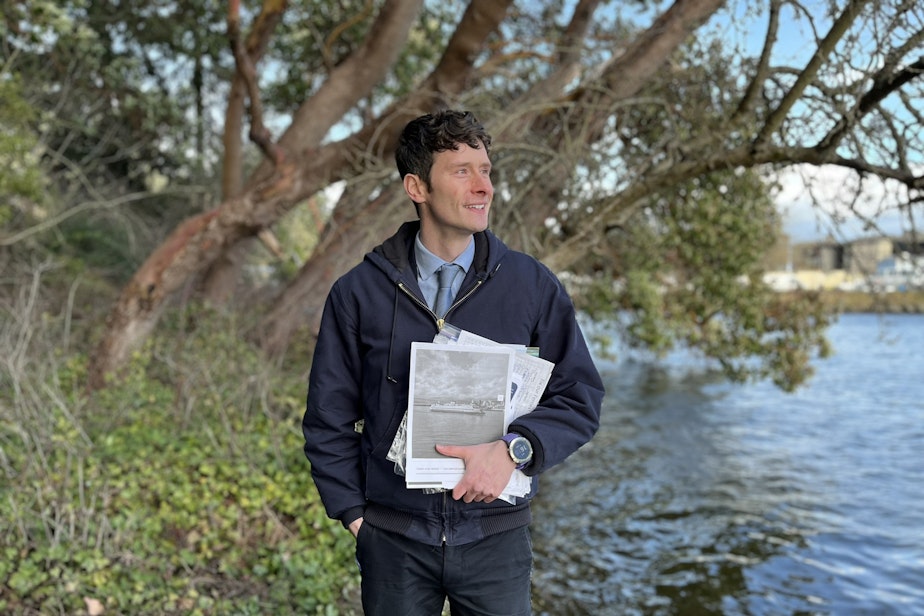

“We are turning the tide here, but it’s going to be a multi-year process — there’s lots of pain and hardship ahead," says State Rep. Greg Nance (D-Bainbridge Island).

Nance says the legislature has released money to pay for five new boats, which should start rolling out in 2028. But the system is going to need 11 more boats in the next 15 years. And with more old boats set to retire during that time frame, it won't be until after the tenth boat is complete that the system starts to see a net gain in boats.

RELATED: Bainbridge Island residents show new optimism and resolve to revive Washington's ferries

Nance says that's too long to wait, and building all those boats will cost way more than Washington state can pay for by itself.

“We need a federal policy and federal funding to rebuild American shipbuilding, to support a maritime workforce across the country, and then to get our ferry networks back up and floating into the future,” he says.

Nance adds that state officials have been trying to strengthen a network of elected leaders across the country who also have aging ferry fleets in their jurisdictions — places like Florida, Staten Island, New York, and the Great Lakes.

“As I've learned more about different ferry networks, we're all way short of what we need,” he says, adding that he hopes they can get more federal funding by advocating together.

In the meantime, the local arm of that effort is ramping up. This week, 38 local elected leaders sent a letter to federal lawmakers asking for help.