A ghost river showed its face during the recent Nooksack floods

Damage along its path offers a hint of what towns could face if it ever came back for good.

The Nooksack River starts in small streams around the base of Mount Baker, and empties into Bellingham Bay on Puget Sound. But a few hundred years ago, it used to flow north into Canada.

In November, 2021, the flooding Nooksack rediscovered that old route north. Only now, there were towns in its path.

We think of the Nooksack as a river belonging entirely to Washington state. Human-built levees help reinforce that perception.

But scientists have been converging around a different conclusion: That over time, the river has done more than just flex its oxbows in some direction or other. It has completely changed direction.

Roland Middleton is a geormorphologist with Whatcom County. He says the signs have been adding up for some time: Unexplained layers of sediment from Mount Baker showing up in Canada. Archaeological sites suggesting the presence of a great river, no longer there.

Sponsored

Then there are the LIDAR maps, detailed scans of the earth's surface created by pulsing lasers. They reveal old pathways the river has taken before, etched in low spots in the landscape.

During November's floods, people spoke of seeing water in places it had never been before. But the water is new to people because most of them settled there after the Nooksack had changed its course.

The Nooksack Indian Tribe may also have knowledge of this time, but we were unable to find a time that worked for an interview.

Middleton says it wouldn’t take much to redirect the whole Nooksack river back towards Canada’s Fraser River again permanently. An earthquake and a landslide in Deming, just a little bit up river, would be enough.

Sponsored

“It will be a tremendous, tremendous effort to put it back to the direction it’s going now," he says. "That’s what I’m trying to convey: This was a terrible flood, and it was a terrible disaster for all those involved. It didn’t spend a lot of time on national news. But if the Nooksack ever gets shoved over and starts to flow into the Fraser again, that’ll get everyone’s attention.”

Middleton uses the description of this geological event to show how dramatic such a change could be. But in some ways, we need to slow down our thinking, and recognize the change that's already occurring.

"In the '80s, as an undergraduate, I kept hearing all these alarmist geologists saying, 'Some day you're gonna see this,'" he says. "Here I am, standing here, telling you, it's not some day — we're seeing it."

He gestures out to the city of Everson, where people are cleaning up after the flood. "There it is."

Sponsored

Everson

Dexter Cunningham had thought his home in Everson near the Nooksack River was perfect.

It was a nice size to raise foster kids, with a big workshop in the back. And it was affordable, which would let him and his wife live debt free as they grow older.

“This place is ideal. Everything about this property is exactly what my family’s been looking for,” he says.

Cunningham’s home sits in a low spot in the landscape, near the outside curve of one of the river's turns.

Sponsored

It's also near the exit point where the floodwaters from the Nooksack began their journey to Canada this fall.

For the first 17 years he lived there, floodwaters surrounded his home many times but never came inside the home. His family would call it a pajama day, and sit around and watch movies, "letting the water do its thing," then spend the next day mucking the mud out of the shop.

But in 2020, for the first time, the floodwaters came 6 inches into his home, and his family had to hop around on furniture, as if playing "the floor is lava."

Cunningham wrote it off as a fluke and repaired his home the best he could.

This year, the floodwaters surged north with much greater force. They ran right through his property and came into his house three feet deep. Luckily, his family had safely evacuated.

Sponsored

In the short term, he's gone through some of the motions of saving his house — performing a four-foot "flood cut" to remove all interior finishes from four feet on down so the house can dry out.

In the long term, his family has struggled to comprehend the pattern he's seeing.

“These floods have caused a strain on my marriage. My wife is ready to move on and be done with this," he says. "I’m still kind of grieving the idea in my head of what my future was gonna be.”

Cunningham’s feelings about his house have changed.

“If we have to deal with the possibility of this every year; we can’t do that. This house shouldn’t be here. People shouldn’t be allowed to live here because of that danger.”

From the Cunningham’s house, the floodwater flowed downhill to Sumas, on the Canadian Border, where it turned a residential neighborhood into a swimming pool.

Sumas

Doug and Sue Miller live in Sumas. During the floods, they took refuge at the border crossing, and were evacuated through Canada.

They ended up staying with a friend.

As the water drained, they made a point of driving through the neighborhood two times a day, just to check on things. Sue was looking forward to moving into an RV in her driveway that her son was setting up for her. Through her car window, Sue told me what it's been like.

“You know, you kind of have to depend on people, and you feel like you’re putting people out," Sue Miller says. "The sad part about that, the people that are taking care of us, they feel guilty that they have a home to go to, and we don’t. It’s a vicious circle for everybody.”

From the passenger seat, Doug leaned over and told me that he's tired of dealing with flood risk. “Like I told my wife – I’d just as soon the thing would have burnt down.”

From Sumas, the waters flowed into Canada, where they caused a billion dollars in damage, pooling near the Fraser River at the bottom of a shallow lake bed pumped dry and filled with farms.

RELATED: Washington's floodwaters revived a Canadian lake wiped out 100 years ago

A new flood map

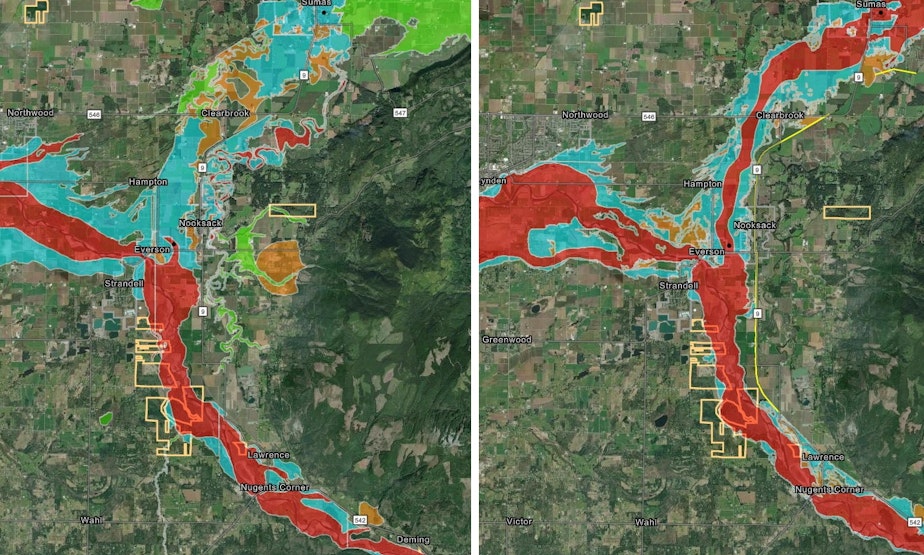

FEMA is drawing up a new floodmap for this part of the Nooksack. And it shows where the water is more likely to flood in the future.

On past maps, the assumption was the levee system would constrain the river to its current path. Those maps assumed that, should flooding occur, water will mostly follow the current path of the Nooksack to the West.

But the new map does not assume the levees are infallible. And it assumes that floodwaters will surge north, following a route remarkably similar to the route the entire Nooksack used to take 500 years ago, when it flowed north permanently.

FEMA is currently negotiating over the details of the map with civic leaders. Next year, they'll have a draft out that the public can comment on.

Changes in the map could have implications for communities like Everson and Sumas, where people like Dexter Cunningham and Sue Miller live.

For one thing, it could make it harder for those towns to grow.

Kyle Christenson is the mayor of Sumas. He says he has concerns with what FEMA's map shows. "We want to do what's best for our homeowners and our businesses. And just accepting the proposed draft map - we had significant concerns because it would be very detrimental."

Jen Perry, an Everson realtor who happens to be married to Everson's mayor, says with the expansion of the floodway on FEMA maps, cities like Everson and Sumas would lose some of their ability to build housing that communities need.

But recent floods may have changed some minds about where those buildings can be built and Perry says that's a good thing. Before the 2021 floods, she says many people didn’t like the proposed FEMA maps. “A lot of people thought this was... overkill. Like this was not really realistic.”

But after the floods, she says many people seem to have changed their minds. Gesturing to the new flood map on the table in front of her, she says “I think most people would probably say that this is fairly accurate.”

That means if Everson and Sumas want to grow, they’re going to have to find higher ground.

What about dredging?

The Nooksack is one of the most sediment-rich rivers in Puget Sound. Its waters pick up rocks and sand on the steep slopes of Mount Baker.

As the river hits flat land, it slows and drops much of that sediment around Everson.

Many people in rural Whatcom County believe the sediment is the root of the problem. They want officials to scoop gravel from the bottom of the river (dredging it), or from its banks, and to raise the levees - so that it can hold more water.

But Whatcom County geomorphologist Roland Middleton cautions against jumping to that conclusion. Increasing the river's capacity in Everson - would lead to more flooding downstream in towns like Ferndale and Lynden. To do it right, you'd have to do it all the way down to Puget Sound, which would have other consequences.

“If we did those things, if we dredged the crap out of the Nooksack, actually dredged it, raised the levees, and just killed every fish on it, what are we going to say to the next generation?”

But the issue of sediment will only get worse over time, Middleton says, due to climate change.

“If you think there’s a lot of sediment in the Nooksack right now – just wait for 20 years," he says. Before, when it snowed on the glaciers, the glaciers would hold that snow and pack down the sediment, slowly meting out what washes downstream.

"Now, the glaciers are going away. And now, what’s in front of those glaciers is more material to be washed down into the river.”

Right now, Whatcom County’s studying a different approach: removing gravel from dry land next to the river. This could let the Nooksack expand during flood season with less harm to salmon.

The county’s waiting for the opinion of the Nooksack Indian Tribe before proceeding.