Big ships transiting North Puget Sound asked to slow down, quiet down for orcas

Big ships entering and leaving Puget Sound will be asked to temporarily slow down to reduce underwater noise this fall. Washington state is importing this strategy from British Columbia on a trial basis in hopes of helping the Pacific Northwest's critically endangered killer whales.

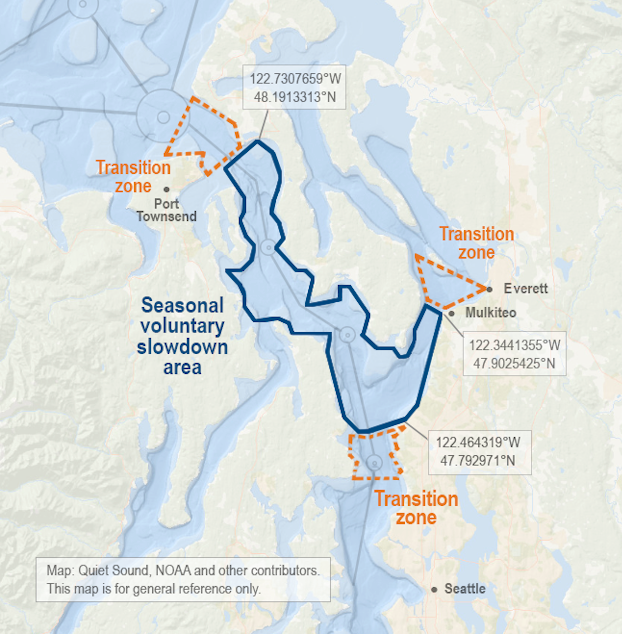

The voluntary slowdown for container ships, tankers, freighters, cruise ships and car carriers is scheduled to run from October 24 to December 22. The slowdown area covers the shipping lanes from Admiralty Inlet by Port Townsend south to Kingston and Mukilteo.

"When large vessels slow their speed they reduce the amount of underwater noise they create and less underwater noise means better habitat for the endangered Southern Resident killer whales," said Rachel Aronson, the program director of Quiet Sound, which is the relatively new, government-funded outfit that organized the slowdown trial.

Aronson said the requested speed reduction varies by vessel type, but for most it would be a 30% to 50% slowdown over a distance of 20 nautical miles. She estimated that participating when it is safe to do so might add between 10 minutes to an hour of ships' travel time, depending on their usual speed.

Aronson said the time period and geographic area for the trial slowdown were chosen because historically, the iconic orcas venture into inland Puget Sound during that window to chase autumn and early winter salmon runs.

Sponsored

Sponsored

"They came in a little bit earlier than the window" on October 4 this season, said Aronson with a smile, before noting the dates of the state's trial slowdown were firmly fixed. "They kind of snuck in under the cover of the poor air quality and fog and showed up just off of Seattle. It was very exciting."

The sleek black-and-white visitors were members of J pod, according to trained observers from Orca Network. The pod stuck around for a couple days and then swam back out of Admiralty Inlet to scout the west side of San Juan Island. J pod returned to inland Puget Sound to forage on October 7 and then departed after three days for points unknown.

The population of resident killer whales in the transboundary waters of the U.S. Pacific Northwest and southwestern British Columbia has dwindled to 73 individuals. Orcas primarily use sound — including echolocation — to hunt for food, orient and communicate. Ship noise can mask the whale calls, effectively blinding the mammals, whose ears in a lot of ways act as their eyes.

Canadian and American government agencies have identified physical and acoustic disturbance as one of the key threats to survival of the fish-eating killer whales, along with lack of prey and water pollution.

Puget Sound Pilots on board, but ferry system not participating

Sponsored

Aronson said a key constituency to win over to the slowdown were the Puget Sound Pilots, who board foreign ships and guide them in and out of Puget Sound ports.

"We’re supportive of the initiative and are interested to see whether the measures benefit the whales," said Puget Sound Pilots executive director Charles Costanzo. "We plan to notify these piloted vessels of the suggested slowdown and ensure that ships are aware of the expectations when encountering whales."

Washington State Ferries leadership was consulted throughout the planning of the trial, too. The ferry system operates three routes on the edges of the slowdown zone: Port Townsend-Coupeville, Edmonds-Kingston and Mukilteo-Clinton. Washington State Ferries Chief Sustainability Officer Kevin Bartoy said the agency is engaged in noise reduction efforts, but is not participating in this experiment.

"It's a nonstarter for us to participate in a blanket slowdown," Bartoy said in an interview. He said the tight schedules the ferries follow would quickly fall apart and lead to "huge impacts" and missed sailings.

"We can operationally slow down when whales are present," Bartoy said. He noted that practice is already standard procedure when ferry crews sight whales or receive whale alerts from the central operations desk.

Sponsored

Aronson said Quiet Sound aspires to make the suggested vessel slowdown more flexible and responsive eventually, so that ships on tight schedules aren't subjected to needless delay.

"In the future, we'd love to slow down vessels in a more dynamic way based on actual whale presence," Aronson said. "But this being the first year, a fixed date was a lot more feasible for our permitting process, for communications and for setting up underwater noise monitoring."

Inspired by Canadians' nearby success

The model for the Quiet Sound trial came from a now six-year-old voluntary seasonal slowdown for large ships in the nearby U.S.-Canada border waters. The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority spearheaded what is known as the ECHO Program to reduce disturbance to endangered resident orcas in their prime summer feeding grounds. This slowdown zone covers the busy shipping lanes in Haro Strait and Boundary Pass adjacent to San Juan Island. In 2020, the project expanded to establish another slowdown zone across Swiftsure Bank, an orca foraging area at the western entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

During a WWU Salish Sea Institute webinar Thursday, Transport Canada senior policy advisor Sonja Henneman described ECHO as a "highly successful program" to address impacts on whales from larger commercial ships. The port authority reported a participation rate by ships in the Haro Strait and Boundary Pass slowdown of 93% between June 1 and September 30, 2022.

Sponsored

Aronson said that after the U.S. trial slowdown concludes, the Quiet Sound leadership committee will gather in the new year to determine whether to repeat the voluntary slowdown, and if so, where and when. The outfit's leadership committee includes representatives from state and federal government, U.S. Coast Guard, tribes, industry groups, ports and conservation groups.

Among the evidence the council should have to review is vessel tracking data, pilotage reports and comparative underwater noise readings from a hydrophone placed off south Whidbey Island.

Copyright 2022 Northwest News Network