Homeowners keep building walls around Puget Sound. Biologists are taking out more

Puget Sound has started getting healthier, at least by one measure: A little less of its shoreline is buried under walls of concrete and rock.

Biologists have long pointed to seawalls, bulkheads and other protective structures known as “shoreline armoring” as a major environmental problem for Puget Sound.

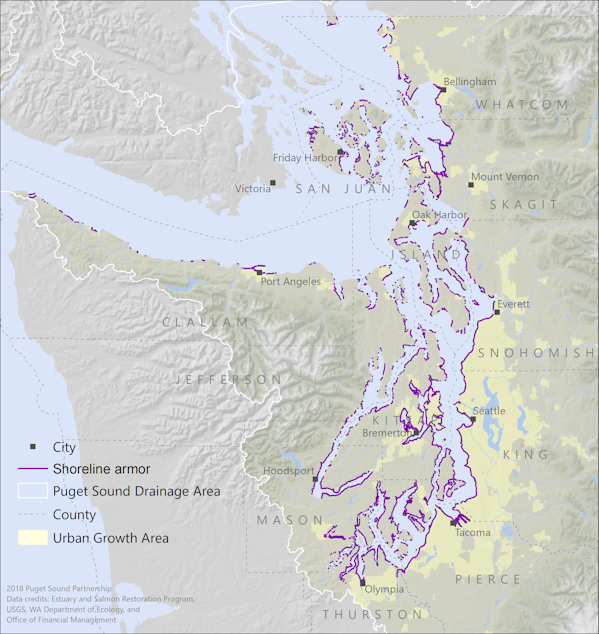

More than 660 miles, or about 29 percent, of the sound’s shoreline have been walled off over the decades, according to the Puget Sound Partnership, a state agency.

Much more of the shore has been hardened in urban regions: Three quarters of King County’s shores and half of Pierce County’s have been armored.

Efforts to remove armoring and restore more natural seaside habitats have had a hard time catching up to waterfront homeowners’ ongoing construction of new armor.

Research by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife shows that single-family homeowners have built 68 percent of the armoring around Puget Sound over the past decade. Half the shoreline losses have been concentrated in just three counties: Mason, Island and Kitsap.

Sponsored

But for the past two years in a row, more walls have come down around Puget Sound than have gone up, according to numbers released by the Puget Sound Partnership in December.

“We’re excited about those new numbers,” University of Washington-Tacoma biologist Aimee Kinney said.

She said beaches unencumbered by concrete and other structures are important for small fishes like surf smelt and sand lance. They form a key part of the underwater food web for species that get a lot more attention.

“Everything eats them,” Kinney said. “They are a source of prey for chinook salmon, which are source of prey for orcas.”

Death by a thousand cuts

The magnitude of the change is small, to be sure: The amount of un-smothered shoreline has grown by less than a mile in the past two years.

Sponsored

Researchers also caution that their numbers don’t show the whole picture, since many homeowners wall off their properties from the water illegally, without getting the required permits. There are more sea walls than permit-based data shows.

While the state’s Growth Management Act and other laws discourage building on critical habitats like shorelines, those laws often go unenforced.

“A lot of the damage happens with these tiny residential-scale projects,” Kinney said. “Death by a thousand cuts.”

Much shoreline restoration has come in big chunks, on state and county parks and other publicly owned land.

Sponsored

“They’re expensive to do, and there’s a lot of work that goes into them,” Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist Doris Small said while working on a shoreline project on McNeil Island. The state-owned island is best known for its former penitentiary, now the prison-like Special Commitment Center for about 200 sexual offenders.

The shores of the lightly occupied island are also an important stopover for millions of young Nisqually River salmon as they head to sea.

“A lot of McNeil Island shoreline is undisturbed,” Small said. “It’s beautiful.”

Crews have hauled away 75 concrete blocks and slabs, 87 creosote-tainted logs and pilings and 500 cubic yards of gravel to expose the beach beneath.

“It was underneath the crushed rock, and we’re finding it,” Small said.

Sponsored

Going soft

Biologists say the big challenge lies in convincing home and vacation-getaway owners to protect their property from Puget Sound in ways that do less harm to it.

Many local governments are encouraging property owners to adopt “softer,” more fish-friendly techniques, like using native vegetation, gentle slopes or anchored logs to deter erosion.

Sponsored

Kitsap County offers grants of up to $5,000 for shoreline restoration and provides free erosion-risk assessments from coastal geologists. While some spots are in real danger of falling into the sea, most shores along Puget Sound don’t need armoring, according to state agencies.

“A lot of people have a perception that they’re more at risk for erosion than they really are,” Kinney said.

Most of the shoreline permits issued by local governments since 2011 have served to replace existing armoring that has degraded over time, according to the Puget Sound Partnership.

Officials say more property owners are exploring how to replace their hard armor with a fish-friendly shore.

Nearly half the permits for new shoreline protection included some of the soft techniques that aim to help Puget Sound even as they keep it at bay.