Walk-in opioid treatment is about to be even more robust in downtown Seattle

Emergency rooms, homeless encampments, and jails.

These are places King County wants to offer medication-assisted drug treatment.

Candidates seeking to represent downtown on the Seattle City Council say they are on board.

Right now, the Seattle Indian Health Board in the International District provides outpatient medication-assisted drug treatment to about 300 people.

Dr. Emily Ashbaugh, the chief medical officer, said someone seeking treatment for opioid addiction can usually begin treatment within a day.

The drug buprenorphine is the central element of this treatment. It helps users get relief from drug cravings while they address their addiction issues.

But access to buprenorphine prescriptions remains a problem. King County said the number of providers has doubled since last year, to 104, but additional action needs to be taken to reach more people.

That level of availability is what the King County Heroin and Prescription Opiate Task Force was pushing for in 2016.

Sponsored

Esther Lucero, CEO of the Seattle Indian Health Board, said these patients can also receive psychiatric, medical, and dental care on-site.

So what’s the next step?

Brad Finegood, of King County public health, said the focus is on enrolling people who aren’t going to their doctor. “We really need to be able to get to the people who are non-traditional treatment seekers,” he said.

This includes people who frequent the Public Health Needle Exchange in downtown Seattle.

King County initially offered treatment-on-demand to 120 patients there through the Bupe Pathways program, which eliminates the attendance and abstinence requirements that can be barriers to treatment.

Sponsored

Finegood said retention and success were comparable to traditional programs.

“That debunked a lot of myths that you have to jump through all these hoops,” he said. “This brought medication to where people were at.”

Now Public Health of Seattle & King County is expanding that program to include up to 500 patients. They’re also expanding to offer medication-assisted treatment in hospital emergency departments, to people served by the Street Medicine team, and to people in or just getting out of jail.

Sponsored

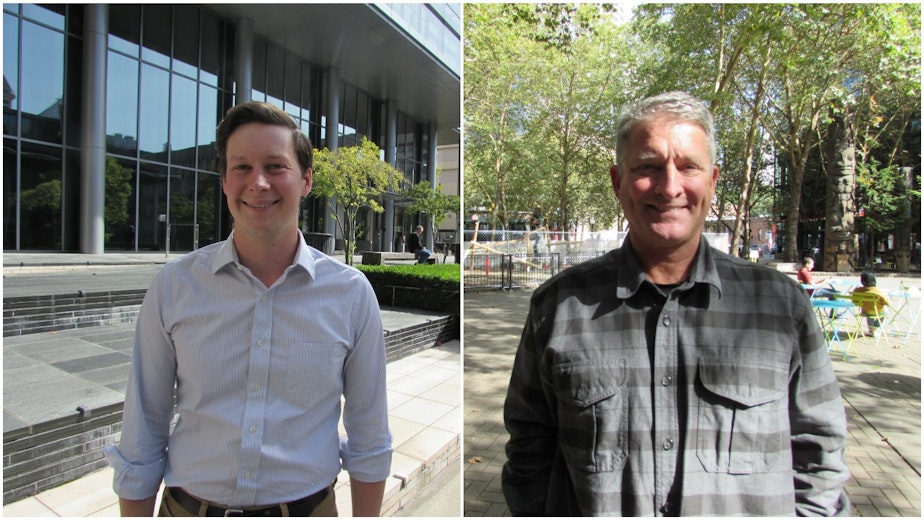

Both candidates seeking to represent Seattle City Council District 7, which includes downtown, have seen the challenges of addiction treatment up close.

Jim Pugel said that, as a member of the command staff at the Seattle Police Department, he supported what’s referred to today as “Housing First.” That was 20 years ago.

“We were able to create what’s known as 1811 Eastlake, which is pre-recovery housing for chronic alcoholics that were homeless and living on the street, and creating a lot of disorder,” he said.

Pugel said his policing background taught him the ineffectiveness of the criminal justice system when it comes to helping people with addiction. That’s why he championed the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD).

Where the program is offered in Seattle, and now in South King County, police connect people with low-level drug or prostitution offenses to case workers and services instead of arresting them.

Sponsored

Pugel said there’s still a need for prosecution, but only rarely.

“There is a small group, 8-12 percent of the criminal offenders, who are non-amenable to anything. They won’t accept treatment, they won’t accept housing unless it’s on their exact tailored terms,” he said.

Pugel’s opponent Andrew Lewis is an assistant city attorney in Seattle, and he said he sees many defendants whose crimes of shoplifting or trespassing are motivated by their drug use. He says many are helped by the LEAD program. But not all.

“In some cases we have folks who have been engaged with LEAD for years, cycling in and out of the municipal court,” Lewis said, “continuing to commit low-level offenses — mostly low level offenses — but a large amount of them.”

For this group, Lewis said he supports creating a "high frequency offender unit" in the City Attorney's office to build criminal cases against them. He also recommends the creation of a municipal drug court, like the one in the Superior Court, to provide another option for structure and accountability while avoiding prosecution.

Sponsored

“When those interventions work, it can be really inspiring,” he said.

King County also wants people to be able to start medication-assisted treatment in jail. They hope to offer prescriptions by the end of the year.

But if people start treatment in jail, they need to have a doctor when they leave. Esther Lucero said the Seattle Indian Health Board is one of the providers working with King County to take over from there. “We’ve been having conversations with the judicial system to be able to provide a warm handoff to a case manager or care coordinator here,” she said.

So medication-assisted drug treatment is expanding in King County. But there are gaps. Lucero said the lack of residential treatment has not gotten enough attention. And increased use of methamphetamines and overdoses linked to the super-potent opioid fentanyl are posing new challenges for public health experts.

There’s currently no buprenorphine equivalent for methamphetamine users.

“If I could develop a medication for methamphetamines, I’d do it in a heartbeat,” Ashbaugh said. “It’s a significantly complicating factor in successful treatment and successful sobriety and recovery. The rates of HIV and Hep C transmission would go way down. And our ability to really effectively address the other aspects of health, including mental health, without confounding factors of meth would be remarkable.”

For more information on addiction treatment, call the 24-hour Recovery Help line: 1-866-789-1511 or visit www.WArecoveryhelpline.org.