Northern State Hospital patients’ grave sites to get memorial, WA money

As early as next summer, Carrie Davidson will be able to read her great-grandmother’s name on a new state-funded monument in a field with hundreds of unmarked graves.

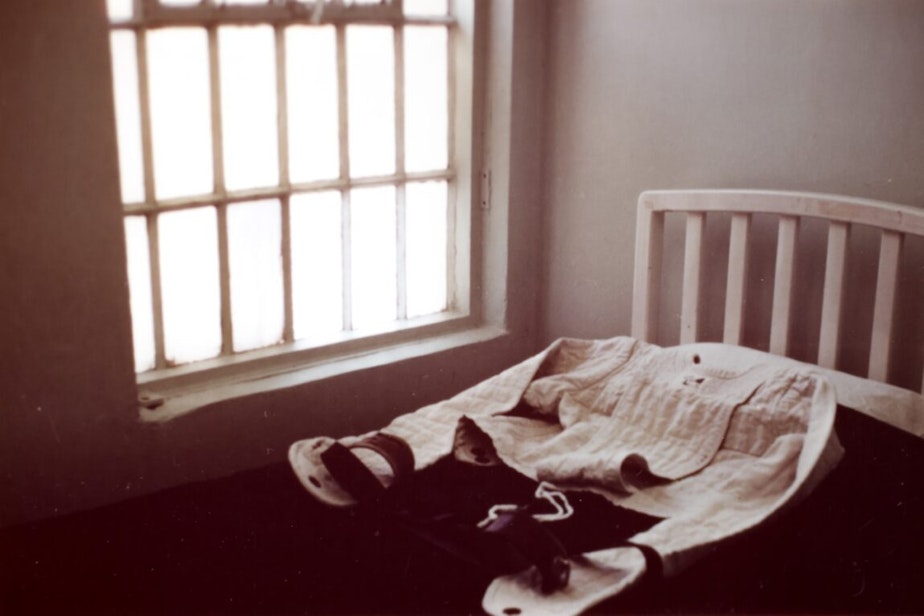

This field is what’s left of more than 1,600 people who were buried or whose ashes were interred at Northern State Hospital, a state psychiatric institution in Sedro-Woolley that was shuttered in the early 1970s. For decades, their names had been lost to history.

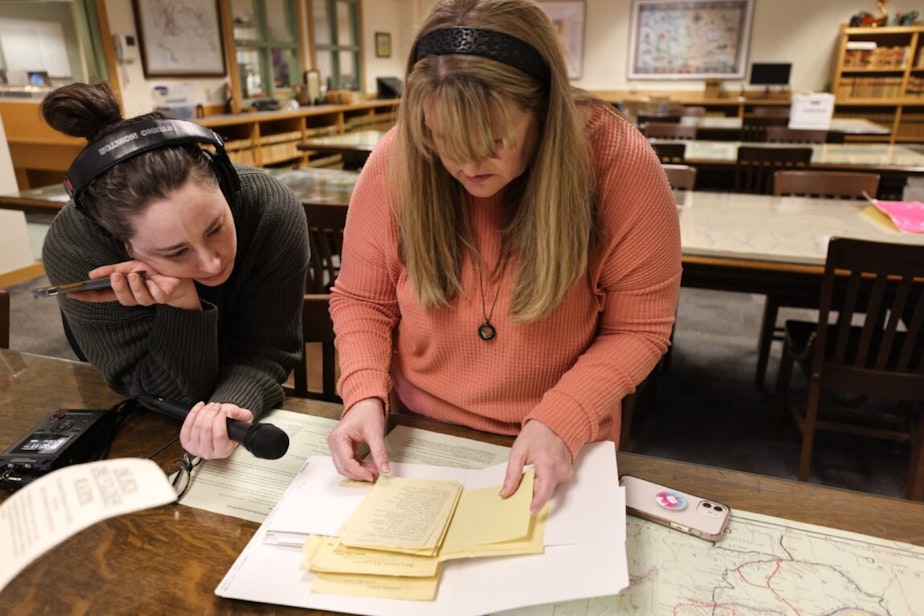

But in recent years, Davidson teamed up with John Horne, an amateur historian with a keen sense of injustice and an obsessive streak who had been researching the grounds and the people buried there. Together, they won the attention of state lawmakers, who secured $175,000 in this year’s capital budget to fix up the burial grounds for patients of Northern State Hospital, many of whose ashes were put in food cans and buried in unknown locations.

“We don’t know where her remains ended up,” Davidson said of her great-grandmother, Lillian Massie, who died at Northern State in 1934 after being institutionalized there by her husband. “So it’s really shining a light onto her in a manner that makes it public, that makes it matter.

“She was a person, she was real,” she said. “She was a daughter, a wife, a mother.”

Sponsored

RELATED: Who was Lillian Massey? A journey to Northern State psychiatric hospital

Horne has spent much of the past five years painstakingly working to match real names to the initials and numbers on the grave markers that do exist at the Northern State Hospital cemetery. He also discovered graves beyond the bounds of the cemetery itself — visible to the naked eye, in grooved hollows near picnic tables by the parking lot.

“The people there deserve far more respect than they’ve ever been given, but that was way over the line for me,” Horne said. “That should have never happened.”

Horne’s mission was a lonely and frustrating one for a long time as the markers he uncovered sank back into the earth with every muddy spring. He credits a chance meeting with a Seattle Times reporter in 2021, and The Times’ subsequent project and documentary film about Northern State Hospital and his work, with winning lawmakers’ attention.

“They saw the story,” Horne said, “and wanted to advocate and get money out of the state capital budget to fix some of the issues that were brought up in that story.”

Sponsored

As part of that project, The Seattle Times successfully pushed the state to release records of patients who had died at Northern State. The Times published these records, and dozens of people identified relatives in them, including families who hadn’t known their ancestors had been institutionalized.

A Seattle Times and KUOW podcast called “Lost Patients” also explored the role of Northern State Hospital in the state’s and nation’s move to deinstitutionalize its psychiatric hospitals and how those decisions continue to ripple through the present-day mental health system.

This summer, “Lost Patients” won the national reporting category for the Livingston Award for Young Journalists, as well as the national Society of Professional Journalists’ Sigma Delta Chi award for narrative podcasts and the Scripps Howard Award for excellence in audio storytelling. The podcast’s honors also include a Peabody nomination, and it has been downloaded nearly 1 million times and featured on national NPR news shows.

Sponsored

After The Seattle Times story published in 2023, Horne and Davidson met with state lawmakers from the 39th district — Rep. Carolyn Eslick and Sen. Keith Wagoner — who visited to learn more about the unmarked grave sites in the Northern State Hospital cemetery. The lawmakers then worked with Sedro-Woolley city officials to prepare the budget item.

Eslick said the experience struck her personally after hearing stories in her own family about a relative who was institutionalized.

“To meet (Horne and Davidson) and see the work that they had already been doing — hours and hours of trying to identify who was there — all it took was a little help to move it in the direction that they needed,” Eslick said in an interview. “And I thought, ‘That I could do.’ ”

Wagoner said he and his fellow lawmakers made a commitment to get state funding at that time because the patients were part of the community and “somewhere along the way in history, the ball was dropped.”

Sponsored

“We’re trying to fix that,” he said. The $175,000 set aside for the city of Sedro-Woolley will be used to create a monument with patients’ names, correct the outline of the cemetery to encompass more graves outside its current boundary and put up a stone wall in character with the rest of the hospital grounds.

Wagoner told The Times that this investment from the state may be just a first step. He is curious about the woods directly behind the field of sunken grave markers, which used to be part of the original cemetery. Horne believes there are human remains of potentially hundreds more patients there.

“At some point, we may need to do some sort of, I’ll call it forensic analysis, or maybe it’s just exploring to see, to see what happened,” Wagoner said.

Davidson said she hopes that when the changes to the cemetery and the monument are complete, visitors will be provoked by what they see. One goal is that these visits create empathy for people and families dealing with serious mental health issues today, she said, and she also wants people to keep talking about the patients’ experiences.

“The people that knew the folks buried in the cemetery, they’re dwindling as time goes by,” Davidson said. “But that doesn’t mean that their stories didn’t matter, that their life didn’t matter.”

Sponsored

This Saturday, the Port of Skagit County and the Skagit County Historical Museum will host a public history day at the Northern State Hospital campus with speakers including two former Northern State Hospital nurses. More information is available at northernstatehospital.org/events.

This story was published in collaboration with The Seattle Times.