Northwest waters buck global heating trend (for now)

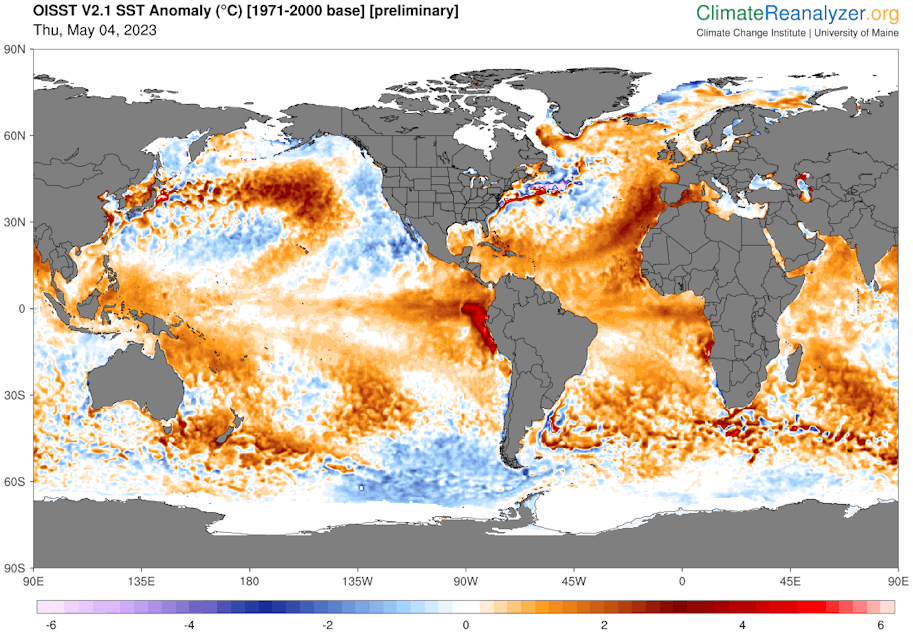

Temperatures in the world's oceans surged to new levels in April, nearing an average of 70 degrees Fahrenheit for the first time on record, according to the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute.

The seas of the world have been warming for decades as atmospheric pollution traps more heat both in the air and underwater.

Much of the U.S. West Coast is bucking the global trend this spring, with sea water staying cooler than its 30-year average.

“It's very clear that human-caused emissions of CO2 is responsible for the warming. That is a global trend,” said University of Washington oceanographer Jan Newton. “But at a given moment, like spring in the Pacific Northwest and Puget Sound, you may not see it.”

Researchers say the much of the North Pacific Ocean is experiencing a heat wave, but at the moment, the blob of heat is staying hundreds of miles offshore.

“So even though the rest of the ocean is very warm, and way offshore is very warm, along the coast, we're actually getting the upwelling, so we're getting those cool waters,” said Andrew Leising, an oceanographer at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration in La Jolla, California.

Sponsored

“You're getting quite a good wind blowing to the south along almost the whole coast. And that tends to cause upwelling,” Leising said.

The winds and upwelling currents have helped keep coastal waters cool and productive for the food web that supports salmon and orcas.

Three years in a row of La Niña ocean conditions also helped the West Coast stay out of hot water. But La Niña is expected to flip to its oceanographic opposite, El Niño, later this year, bringing warmer waters to the West Coast. That could put marine life back in the hot seat.

RELATED: El Niño is coming. Here's what that means for weather in the U.S.

Leising said three years of favorable ocean conditions have boosted populations of key species along the West Coast, which may help nearshore ecosystems endure hotter temperatures when they do arrive.

Sponsored

“Towards Central and Southern California, we have more anchovy than we've seen in a long time. That is the base of the food web and super critical,” he said. “Hopefully, the food web is kind of going to have some resilience.”

Of course, what happens in the ocean doesn’t stay in the ocean. Coastal water temperatures have major consequences on shore as well.

“The circulation of the oceans is what affects our weather. So it's not just if you care about marine organisms [that you should pay attention to ocean warming], it's also how that can be very disruptive to the weather patterns that we are used to on Earth,” Newton said.

“In California, we rely on those cold ocean temperatures to have a nice coastal climate for us to live in,” Leising said. “If the waters were much warmer, we would be like more like Florida. It would be much, much hotter on the land, say in California and probably even parts of southern Oregon.”

Water expands as it warms, and warmer seas, whether fueled by human pollution or shorter-term El Niño conditions, generate higher sea levels.

Sponsored

“I would not be surprised if we have strong storms coupled with an El Niño various places all up and down the West Coast this year that then get coastal flooding,” Leising said.

He said it’s unclear whether the exceptionally warm April in the world’s oceans is just the Northern-hemisphere spring arriving a bit early or a sign that ongoing global warming may be intensifying.

“Just because it's warm by a few tenths [of a degree] a little bit earlier, to me, that's not a ‘stop the presses’ kind of occurrence,” Leising said. “It seems a little premature to really get worked up about this.”

Oceans have absorbed most of the extra heat retained by the Earth as the global climate heats up — essentially doing humans and other terrestrial organisms a massive favor by tamping down the pace of warming on land.