More tankers in orca waters as oil exports to China increase

Crude oil exports from Canada’s Port of Vancouver shot up by at least 67 percent last year, sending more tankers through critical habitat for orcas on both sides of the Washington-British Columbia border.

Most of the oil in the Trans Mountain pipeline from Alberta to Vancouver winds up in refineries in Washington state, by way of a branch pipeline to Ferndale and Anacortes.

Much of the rest goes to a refinery in Burnaby, B.C., just east of Vancouver, that produces gasoline, diesel and jet fuel for Canadian customers.

Energy analyst Kevin Birn with IHS Markit in Calgary said people in the Vancouver area used less of those products last year, leaving more oil in the big, multi-customer pipeline to be sold overseas.

“Any free space will be occupied by exports at this point,” Birn said. He said data from the National Energy Board of Canada shows exports from the Trans Mountain pipeline doubling last year, more than the 67 percent increase reported by the Port of Vancouver.

Most of the oil sent overseas went to China and South Korea.

Sponsored

The Vancouver Sun first reported on the surge in exports.

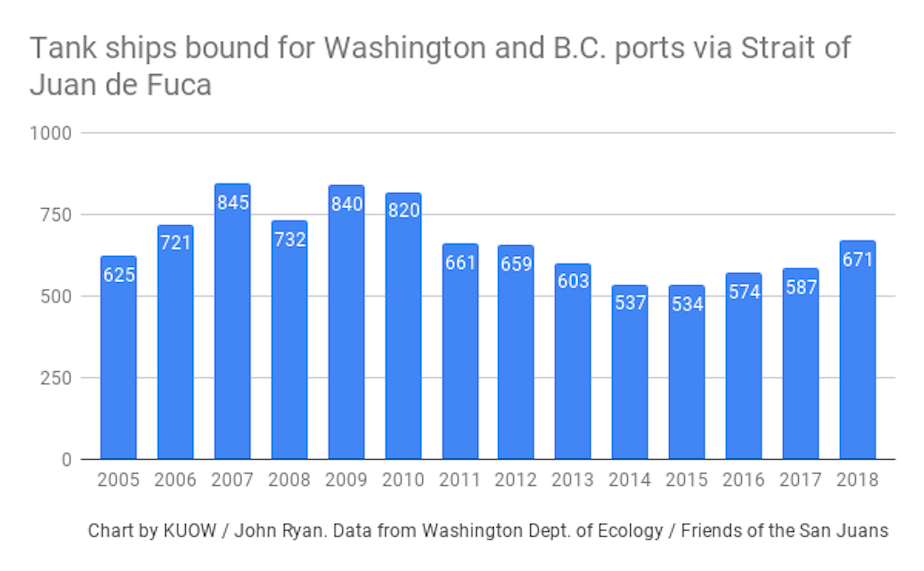

It’s meant a jump in oil tankers in Washington waters – and more risk of oil spills – though fewer tankers ply our waters than did a decade ago.

About half the oil used in Washington state is delivered by tankers coming in the Strait of Juan de Fuca from the Pacific Ocean.

The shipping route from Vancouver to Asia snakes along our region’s watery international boundary: around the San Juan Islands and out the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

State officials said that Canada is less prepared to handle or prevent oil spills than Washington.

Washington Department of Ecology spokesperson Sandy Howard pointed to the emergency response tug stationed at Neah Bay, near the ocean entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

“That’s something that Canada does not have,” she said. “We have built out a very strong oil spill prevention program in our state.”

The Neah Bay tug helped a 984-foot cargo ship stay off the rocks on Tuesday. Nearing the end of its voyage from Tokyo, the NYK Apollo lost power in the strait and started to drift toward Shipwreck Point on the Olympic Peninsula.

Sponsored

“It’s really been a very helpful prevention tool for Washington state,” Howard said of the Neah Bay tug.

In at least one way, Canada is more careful about oil-spill prevention than Washington state: It requires tugboat escorts for smaller oil tankers and oil barges that can travel unaccompanied through Washington state waters.

Such barges carry Alberta oil from the Port of Vancouver to the U.S. Oil refinery in Tacoma.

The Washington House of Representatives and, on Tuesday, the Washington Senate’s environment committee have passed legislation requiring escort tugs for small oil tankers as well as large ones in Rosario Strait, the busy waterway east of the San Juan Islands.

The legislation would also start a rulemaking process to establish escort tug requirements in other “high-risk” waterways.

Sponsored

No jurisdiction requires escort tugs for any tankers in the 10-mile-wide Strait of Juan de Fuca.

A major oil spill could have catastrophic consequences for marine life in the Salish Sea, shared by Washington and British Columbia, including its 75 remaining southern resident orcas.

Ship noise also makes it more difficult for orcas to echolocate their increasingly scarce prey.

“Any major increase in shipping pushes them closer to extinction,” campaigner Sven Biggs with the environmental group Stand.Earth said in a tweet.

“It’s a very small portion of all vessel movement in the Salish Sea,” pipeline company Trans Mountain tweeted about tanker traffic serving its pipeline.

Sponsored

Cargo ships outnumber oil tankers in the Strait of Juan de Fuca about 6 to 1, according to Canada’s National Energy Board.

The Lummi Nation, whose reservation sits about 10 miles south of the Canada border and whose tribal members consider orcas their relatives, have called for a moratorium on any projects that would increase shipping traffic in orca habitat.

The government of Canada plans to triple the Trans Mountain pipeline’s capacity.

According to the National Energy Board, that project would increase overall tanker traffic in the Strait of Juan de Fuca by 60 percent and nearly double it in Haro Strait, critical habitat for endangered orcas off the west coast of San Juan Island.