Seattle's overlooked climate impact: Shopping

Seattle's impact on the climate in recent years could be a lot worse than the city acknowledges.

A new report from C40, a global coalition of large cities including Seattle, says the cities' greenhouse gas emissions are 60 percent higher than previously reported.

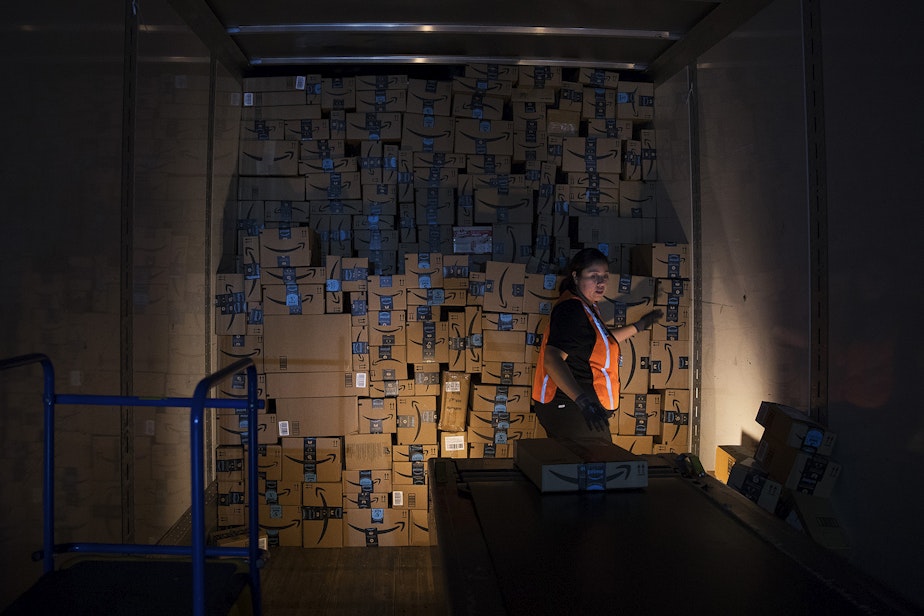

That's because cities generally pay little attention to the impacts of goods consumed locally but made elsewhere.

Most things bought in Seattle weren't made in Seattle.

“Environmental impacts mostly come from stuff we buy, maybe 90 percent,” said Rita Schenck of the Institute for Environmental Research and Education on Vashon Island. “The environmental impacts of mining, manufacturing and transportation to get you your can of soup are bigger than the environmental impact of heating that can of soup or throwing that can away.”

Sponsored

China has surpassed the United States as the world's leading climate polluter, in part by manufacturing products that are consumed in Europe and North America.

"A lot of the environmental footprint in the U.S. comes from China," Schenck said.

The C40 report only addressed overall trends and did not specify which of the 79 cities it studied had the worst emissions.

"The purpose here is not to focus on individual city emission profiles," the report states.

"North Americans consume more than folks really anywhere in the world, so we know that we need to be doing better reducing our own consumption and buying locally wherever and however we can," said Jessica Finn Coven with Seattle's Office of Sustainability and Environment.

Sponsored

Finn Coven said products made in the Northwest do less harm to the atmosphere because our electricity is quite clean. Other regions rely much more on climate-harming power sources like coal or natural gas.

Yet Seattle's Climate Action Plan doesn't address consumption, even though that's where most of our carbon dioxide emissions come from.

An exception, Finn Coven said, is the city's programs to connect low-income residents to local sources of fruits and vegetables.

She said it's harder for government to influence consumption than things that shape local energy use, like our building codes or transportation infrastructure.

The last time city officials tried to tally all of Seattle's climate impacts was seven years ago.

Sponsored

They found the average Seattleite adds 140 pounds — nearly their own body weight — in carbon dioxide to the sky each day.

That's less than the typical American, but about five times higher than the global average.

Seattle's most recent greenhouse gas inventory, which doesn't account for emissions from food, electronics or other things Seattleites consume, puts that figure at just 50 pounds of carbon dioxide per Seattle resident per day in 2014.

Schenck specialized for decades in "life-cycle analysis" — studying the cradle-to-grave impacts of consumer goods. As a U.S. negotiator, she tried in 2012 to incorporate carbon emissions into the standards that govern international manufacturing and trade.

"Then we could say we aren’t going to accept these kinds of products that have high carbon footprints," she said.

Sponsored

That could have caused major disruption in coal-dependent economies like China and India.

"China organized a bunch of developing countries to shut it down," Schenck said.

As a result, governmental efforts today to penalize or avoid the importing of high-carbon products to help fight climate change could be blocked as unfair barriers to trade.

Schenck said she is now semi-retired and running a goat farm on Vashon.

"I spent my entire career trying to educate people about that, that our impact comes from the things we buy," Schenck said.

Sponsored

"It’s been a frustrating 30 years," she said.