Reporter's notebook: tending to childhood scars in a pandemic, both old and new

“Tell us a Walter Higby story!” Growing up, my siblings and I begged my dad for these homespun bedtime stories about a mischievous, wayward boy who dodged trouble on the streets of Portland, Ore. We gaped at Walter’s adventures with his sidekick, Birdbrain Clamshell II.

Their Scooby Doo style capers included a break-in at a soda pop factory so they could ferry cases back home, and trespassing on a naval ship in the boatyard. I remember the stories featured a lot of running from grown-ups.

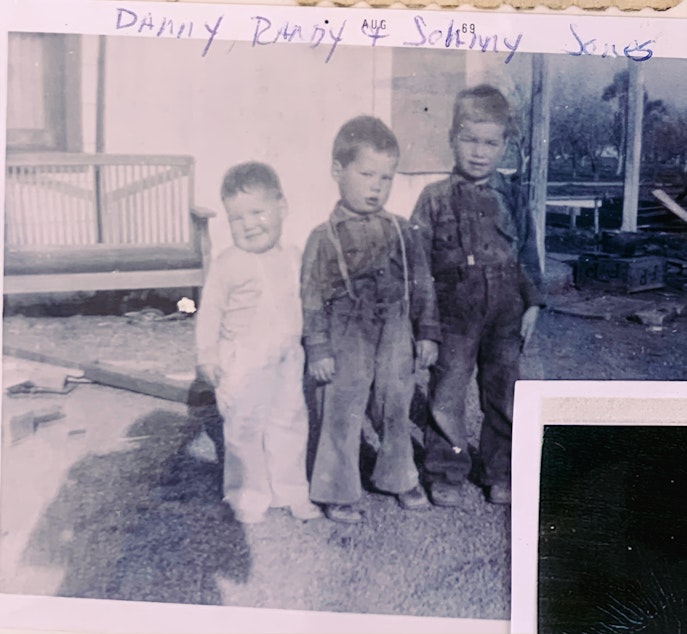

Of course, I figured out later that Walter Higby was my dad. The sidekick was likely my Uncle Danny, who’s still fond of wild schemes and phrases like, “Look, here’s what you need to do.”

These were the stories my dad chose to tell us. The others, we pieced together later.

Over the years, I’d learn my dad and his six siblings spent several years in state care — some group homes, some foster families, some juvenile detention. Their father (my grandfather) was a kind man but also an alcoholic who only occasionally lived at home. He died in a car crash when my dad was in high school. My grandmother had grown up in an orphanage, and spent much of her parenting years moving between low-wage jobs and welfare. But perhaps what most defined her was her devotion to her kids, doing whatever she could to keep them safe.

Sponsored

My dad would never have labeled his experiences growing up as childhood trauma — it didn’t seem to affect him in that way. His was just a kind of tough luck he saw all around him as a kid living in a poor neighborhood in the 1950s. When I became a parent myself, I started to see his childhood stories differently, and I began to wonder whether they might explain some things I'd observed about my dad later in life. He mentioned recently that a lot of boys he knew back then ended up dead or in prison at a young age. Maybe he counted himself lucky. Although none of it, really, boils down to any kind of luck.

Through these pandemic years, the question of how early hardships affect a child has been on my mind and the minds of so many parents I know. The pandemic has especially amplified concerns about families in vulnerable situations — at the edge of their stress tolerance — and young children at increased risk of abuse, neglect, violence, instability, or a dysfunctional home life. The toll will be measured for years to come, and health care providers sounded the alarm early about needing to build up resources now to meet the long-term needs of this affected generation. How might this adversity, toxic stress, or trauma show up in their physical and mental health? What strategies can mitigate harm and help these children grow into healthy adults?

These were questions I’d long had about that boy from Portland who’s now my 77-year-old dad. The questions got louder for me once I became a parent and began to wonder how my parents’ childhood scars shaped what they passed on to me, and what I might pass on to my son. The volume went up again during the pandemic, as I thought about families with generational trauma and how times of crisis can reactivate old stress responses or coping behaviors, ranging from emotional withdrawal to substance abuse. In other words, how would the pandemic exacerbate childhood traumas, both new and old?

“As we've seen, it's bringing out what we know that's been true for hundreds of years in our society, that those who are most vulnerable continue to be most vulnerable,” said Mark Fadool, a mental health therapist who worked with children and families at Seattle’s Odessa Brown clinic for decades. “The folks that have had the hardest pathway to access to good care continue to have the hardest access to good care, whether it's health care, therapy, education, nutrition, housing — all the social determinants of health.”

Sponsored

To be clear, I am not in this vulnerable category and it feels awkward to let my personal story take up space here. Yet, because my family’s recent history crosses this territory, it seems honest to grapple with my backstory as I report on this broader issue of childhood adversity and ask families to open up.

I

knew I needed to rope my dad into an uncomfortable conversation — uncomfortable for me, anyway. I wanted to ask him to fill out a questionnaire about his ACEs, or Adverse Childhood Experiences. A standard 10-question survey is used to measure these early life experiences, ranging from abuse, neglect, violence, loss of a parent, or living with someone who abuses substances or is mentally ill. Decades of research shows that the higher your score, the higher your risk for later health problems.

I was curious how my dad might score and what we might learn. In our family, we’ve never talked much about these things. I stewed about the conversation for months and almost chickened out, but I’m tired of chickening out on tough conversations with the closest people in my life.

One weekend last December, I saw my opportunity.

Sponsored

My dad had stopped in for a visit to our home in Seattle, and, surprisingly, he stayed for a second night. He mostly lives in Boise now, since the day after my mom’s funeral when he packed up his Prius and left their longtime home of Los Angeles. I printed out the ACEs survey. I rehearsed how I’d ask him. Still, I let most of the weekend go by with this question nagging at the back of my mind.

I noticed, though, how he seemed a bit softer, more reflective since my mom died in 2018. He’d also become somewhat more talkative, or maybe it was just that she was no longer around with her running chit-chat about the day-to-day lives of her and my dad, their nine grandkids, my two brothers, my sister, the ladies in her prayer group, the neighbor kids who come by for popsicles, and on and on. She used small talk to pass the time, but getting to know you was her true prize. She found us all endlessly fascinating. I’m more of my dad’s daughter in this way, generally allergic to chit-chat and with a higher bar for fascination. I’m not saying that’s a good thing.

That December weekend, my dad continued to surprise me. “Oh sure, of course,” he replied with zero hesitation when I asked if he’d take the survey.

I’d steered him into the home office we built in the backyard during the pandemic, where he looked quite tall in my “it’s not a She Shed” space.

I’d only given him a brief explanation about ACEs, telling him about my current reporting project focused on childhood trauma during the pandemic and solutions to reduce harm. I told him how my project would also explore the ways a parent’s own ACEs can influence their parenting, particularly in times of crisis. My dad nodded along as I rambled. He got it, of course. My shoulders relaxed.

Sponsored

“I have a hunch about a couple that are on the list,” he mused. “I’ll do it right now.”

I handed him the one-page form and he sat down on the couch, grabbed a pen, and started to check the boxes “yes” or “no.” I pretended to type an email while he finished the survey. The scratch of his pen broke up the silence.

“I got three and a half, Lulu” he finally announced. “What does that mean, that I’m almost normal?”

“I

t means you should hug your dad,” joked Fadool, the therapist I consulted about ACEs, when I casually put the question to him.

Sponsored

My dad is not known for his hugs; it was something of a running joke in my family that my mom had to teach my dad how to hug. He’s still partial to a quick squeeze from the side.

But Fadool also warned against putting too much weight on anyone’s ACE score alone, at least in terms of how it might show up in someone’s behaviors later in life, including parenting. “It's a tricky question because none of this is linear. You could have one ACE, and it could be just a massive ACE that really impacted one's ability to parent and to be present as a parent. Or you could have eight ACEs and be an amazing parent.”

My dad was an amazing parent — coaching little league, building a ‘secret’ playroom cubby under the stairs, putting us through college. My question about his adverse childhood experiences centers on how those early years possibly affected his ability to form attachments and get close to people later in life. He’s rather partial to his alone time. My mom was the emotionally expressive one, the one to turn to for heart-to-heart talks about feelings or life’s twists and turns. I, too, am partial to my alone time. And I suppose that’s the crux of it — I want to notice and change these family patterns that might affect our bonds.

My dad’s demeanor wasn’t uncommon for people in his generation. “A lot of times they were told, 'stuff your emotions,' especially the ones that are really uncomfortable,” Fadool said. “There's nothing good that comes out of that.” He’s hopeful that more kids growing up now can hear a different message: “'You have emotions, learn how to express them, and express them well without hurting yourself or others.”

Role modeling is key, Fadool said. He also emphasized the power of repair when we inevitably mess up.

“Being able to say to your kid or your spouse, or whomever, ‘I understand that I hurt your feelings and I’m sorry I said that. My bad. I will try not to do that again.’ That dance of repairing teaches kids so much, and we have plenty of opportunity as parents to work on [it], which is a good thing.”

Just like any dance move, it takes practice to get the rhythm.

M

y dad’s bedtime stories always ended in one of two ways — “poor, poor Walter Higby” or “bad, bad Walter Higby.”

Those pat ending probably hide the messier details from his time in the juvenile detention system, but overall things turned out alright for Walter Higby. (And also for his sidekick Birdbrain Clamshell II.)

If you think of ACEs on one side of a scale, protective factors give weight to the other side.

“If we were doing the reverse, all the positive influences, I’d probably get a 12,” my dad said that winter afternoon in my office, after we tallied his ACEs score. “I consider myself to be a very fortunate kid because looking back at all the places I was and the people I was around, it could’ve been bad.”

He knows, without a doubt, what shifted the balance for him: his mom. She was always his home base, even when they couldn’t make a home together.

As we reviewed the checkboxes on his form, he stirred up a memory about his mom’s homemade bread, and how his friend Floyd liked to come by for a slice served up with butter and a sprinkle of sugar.

When my dad got in trouble, he could count on her to smooth things out with the judge, who knew her on a first name basis. She always made sure he landed OK. He has also credited the group home where he lived the first two years of high school as a turning point, and a place where he found structure and support. The foster placements the next two years were less great. “There’s lots of folks that have lots of trauma in their past history that are extremely resilient, they had someone in their corner, and they've kind of worked things out,” Fadool said.

He stressed the importance of working with families early, when kids are young, to build these relationships and ensure every child has someone in their corner, whether it’s a family member, care provider, or friend. Fadool described that relationship work between a caregiver and child like sonar, listening and responding to each other. “Going back and forth and back and forth. And if we're not working on increasing our reflective capacity, then we don't have the ability to be as present, which can cause attachment issues,” he said. When individuals, families and communities have space to reflect, he said, that’s when growth and learning happen. “It’s that complicated and that simple.”

In many ways, the pandemic has set the stage for what we might call "The Great Reflection" -- a time to find fixes for our frayed social safety nets that are supposed to keep kids safe.

For me, it brought some relief to broach this deeper conversation with my dad, and to explore these threads of his early experiences and relationships. Through talking about our family stories, I’m able to grab on to him a little more — and fully embrace the power of a side hug.

Liz Jones is a 2021-22 fellow with the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism. This story is part of an ongoing project focused on solutions for childhood adversity and trauma connected to the Covid-19 pandemic. If you have a story you’d like to share, please email her at ljones@kuow.org.