What kind of Democrat do Seattle voters want running their city?

The mayor’s race between M. Lorena González and Bruce Harrell is a battle to reinvent Seattle’s future. It also exposes an increasingly bitter divide on the left.

Seattle’s largely progressive electorate, still hung over from the traumatic 2020 election and recovering from the pandemic, will have to decide if it wants Harrell to steer the city more towards the center lane on key issues like policing and homelessness, or for González to drive it further left.

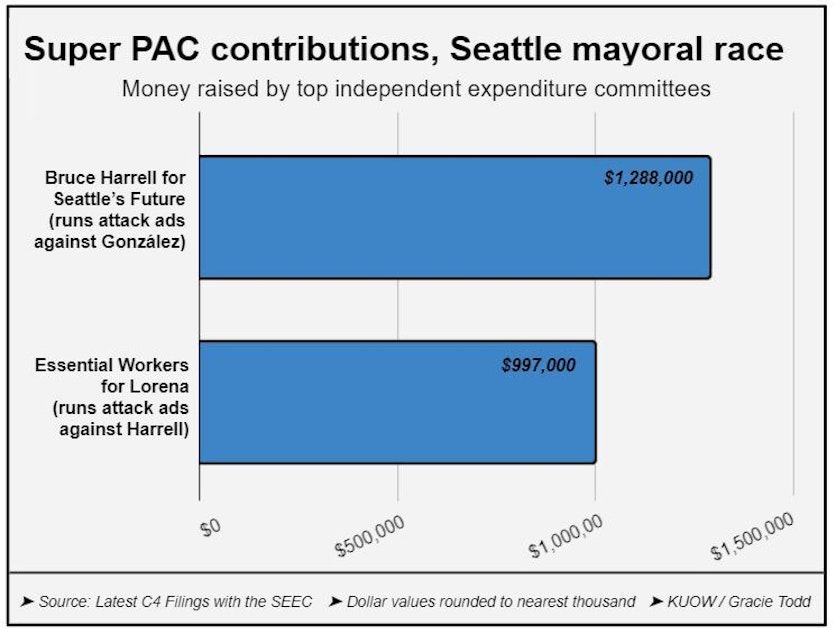

Voters will have their work cut out for them in trying to make informed decisions. That’s partly due to the hundreds of thousands of dollars being spent on one-sided mailers and the tone of misleading attack ads, (not to mention some of the more venomous posts on Facebook and Twitter), all of which tend to imply Lorena González and Bruce Harrell are polar opposites.

While there are some key differences, you’d never guess from the tone of the attacks that the two also have a lot in common. Both Harrell and González are lifelong Democrats whose politics were shaped in part by the racism they and their families faced growing up in Washington state.

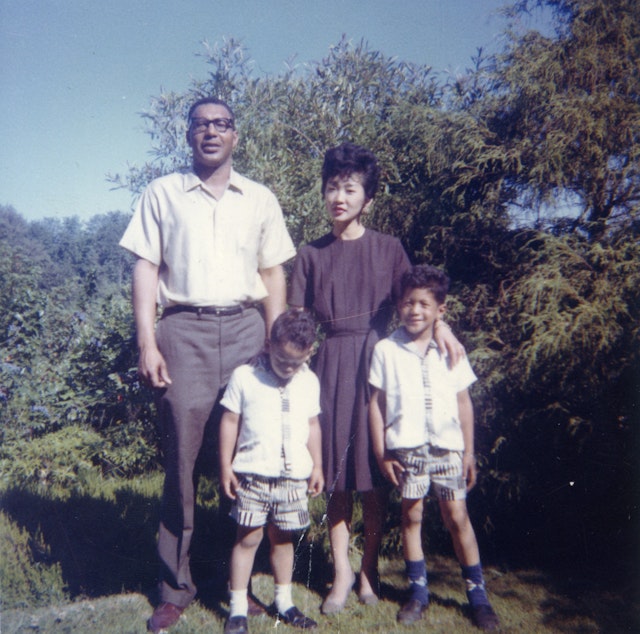

González talks about being “the child of migrant farmworkers” from central Washington where she “earned her first paycheck at the age of 8,” and Harrell speaks of growing up in Seattle’s “redlined central area.” His dad was Black, “from the Jim Crow South” and his Japanese-American mom faced internment during WWII.

The two candidates went on to become lawyers. After receiving her law degree in 2005, González became a civil rights attorney. Harrell started out in corporate law, but in the late 1990s started a firm where he practiced civil rights and employment law.

Sponsored

Later, the two overlapped on the Seattle City Council after González was elected in 2015 and until Harrell stepped away in 2019. While they sometimes disagreed, they often championed the same issues.

Back in 2017, for example, Harrell sponsored a “Bias-Free Policing Law,” noting in council discussion that a Black friend had recently been stopped for a minor traffic infraction.

“That incident resulted in three officers, one hand on a gun, and barking dogs,” Harrell said. González commented that Harrell had “very articulately” made the case for changing how officers interact with “protected classes” in Seattle in instances like that where there were no monetary damages, and no clear legal remedy.

There were differences, including their style of leadership in city government. González earned a reputation with staff for being a very active council member who takes a hands-on approach to legislation. Bruce Harrell was seen by staff as laid back.

Sponsored

Like the left-leaning Democratic electorate of Seattle itself, the candidates also split in the 2020 Democratic primary. Harrell backed Joe Biden. González voted for Bernie Sanders.

That difference is also reflected in who they listen to in and outside the city power structure. In general González has closer ties with organized labor and the activist left. Harrell also listens to labor and activists, but business also has his ear. These divisions are also reflected in who is backing their campaigns this year.

In subsequent years the City Council moved further left, and more protests moved off the streets and inside city hall, over issues like police sweeps of homeless encampments in public spaces such as parks. The gap among Seattle Democrats and between Harrell and González widened.

Sponsored

Last year, González helped kill Mayor Jenny Durkan's approach to engaging homeless encampments known as "Navigation Teams," a program that dates back to Mayor Ed Murray's final year in office in 2017. The idea was to pair social workers with police officers to offer help and services, and ultimately to also clear encampments.

This year on the campaign trail, González has said she would not sweep anyone sleeping in tent encampments.

“Forcibly removing people from one place to another place of the city, which is how the city has currently led on the issue of trying to address the homeless, is not what people want to see” she said.

Harrell would remove some encampments.

“We are not criminalizing those who need help, we're acting as we should,” he said.

Sponsored

Their homeless plans are different (more on González's plan here, and Harrell's here), but in general, both would spend more money on things like housing and services to help homeless people. And both candidates have said they’re open to raising progressive tax revenues.

But when it came to a proposed business tax hike in 2018, Harrell did not go as far as González. This year, he’s being heavily backed by real estate executives and other wealthy individuals.

Then there’s the question of how to reform policing. Following the protests against police bias and violence last summer. González led the Council in cutting the Seattle's Police Department's budget by 20%.

At the time, she disappointed portions of her activist base by not following through on promises of cuts of 50% or more. But this year as a candidate, González has indicated that she is still open to that goal 50% reductions in the police budget.

The campaign has emphasized, however, that any future cuts would be tied to other investments, which are also designed to protect public safety.

Sponsored

“I think investing in those alternatives to law enforcement, and at the scale needed, is going to be important to allow the police department to focus on the most serious crimes in our city,” González said.

Current police staffing levels are below what they were a few years ago. Around 300 officers have left the Seattle Police Department in the last year and a half.

For his part, Harrell said he would look towards hiring more cops to help improve public safety in a city where shootings and violence have skyrocketed in recent years.

Harrell also said he would work to change the Seattle Police Department, away from the same culture of tolerance for misconduct that also led to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

“If they [members of the SPD] can't say that that kind of inhumane treatment shouldn't be happening here in Seattle then they shouldn't be on the force,” he said.

On that, and nearly every question, the two candidates reflect the shared values and different shades of blue now vying for control of the Democratic Party locally, and nationally.

The question for Seattle voters this year is: What kind of Democrat do they want running their city for the next four years?