Ship that spilled 100+ containers could have ridden out the storm in sheltered waters

The ship that spilled more than 100 shipping containers off the Washington coast was in a holding pattern on the open ocean when it could have ridden out the storm in more sheltered waters.

Inflatable toys. Floor mats. Rubber boots. Baby oil. Chinese checkers. Dozens of refrigerators.

Just some of the garbage marring one wilderness beach on the west coast of Canada’s Vancouver Island after four shipping containers washed ashore there and one of them broke open.

The defaced coastline was one aftermath of the freighter Zim Kingston spilling an estimated 107 shipping containers into the Pacific off the Washington coast five days earlier and 200 miles to the south.

A day after the container spill, the storm-tossed ship caught fire at anchor outside Victoria, where two more containers reportedly went overboard. Containers of tires on board continued to smolder Thursday evening.

Port Hardy schoolteacher Jerika McArter took her class of 8th through 12th graders from Eke Me-Xi Learning Centre for their weekly field learning class to a beach near Cape Scott Provincial Park and the northwest tip of Vancouver Island.

Sponsored

“We go out every Wednesday to learn on the land,” she said in a text message to KUOW. “Different destination every week, learning about the land we live on, what habitats it [has].”

McArter said they weren’t prepared for what they ran into.

“At first we didn’t realize the extent, so it was kinda exciting,” she said. “But when we walked further down the beach there was a lot of shock, fear of what will happen with all this stuff, how many years it will take to clean this all up, sadness, anger. In the waves you could see more debris floating around, just really overwhelming all of it.”

Canadian Coast Guard officials said Thursday they had spotted one of the four beached containers refloated by the tides and carried to the vicinity of Cape Sutil, the northernmost point of Vancouver Island.

Sponsored

Two of the 109 lost containers are known to hold combustible, hazardous materials: potassium amyl xanthate, used in mines and pulp mills, and thiourea dioxide, used to manufacture textiles. Canadian officials say the four containers that washed up near Cape Brooks did not contain those materials.

According to drift modeling by Environment and Climate Change Canada, any containers that haven’t sunk to the bottom of the ocean by now are expected to keep floating north.

Under Canadian law, the ship’s owner, Danaos Shipping of Greece, is responsible for the cost of cleanup and firefighting.

“To date, Unified Command is satisfied with the actions taken by the owner both at the ship itself, and in efforts to recover the containers and debris,” a Canadian government press release stated Thursday.

Salvaging any sunken containers could be a difficult operation, and not just because containers likely sank over a wide area as some of them drifted north. The continental shelf near where the containers went overboard is 450 to 600 feet deep, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration nautical charts. The charts also show “unexploded ordnance” and “unexploded bombs” as well as submarine cables running along the sea floor in the area.

Where the troubles began

Sponsored

The Zim Kingston, owned by a Greek company, chartered to an Israeli one, and sailing under the Maltese flag, had steamed across the Pacific from South Korea at about 11-15 knots (13-17 miles per hour) on its way to Vancouver.

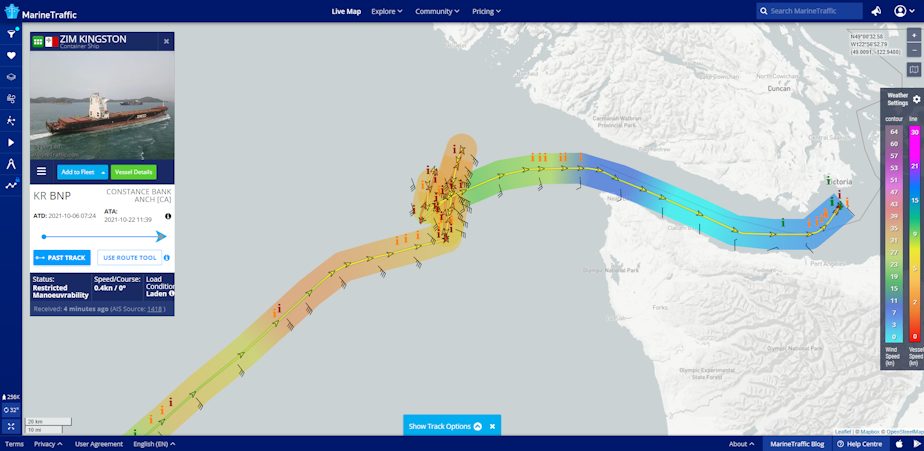

Brian Young with Canada’s Pacific Pilotage Authority said the Zim Kingston’s shipping agent had requested an anchorage at Constance Bank, about 4 miles south of Victoria, long before the ship neared the coast of North America.

On Oct. 19, two weeks into its transoceanic voyage, the Zim Kingston received faxed permission to anchor at Constance Bank, according to Young, with an ETA of 5 p.m. on Oct. 22.

The cargo ship was still more than 500 miles and three days out from its predicted arrival at the anchorage.

Before dawn on Oct. 21, the container ship slowed to 3 knots, about the speed of a sea kayaker. It was roughly 40 miles from Cape Flattery at the tip of the Olympic Peninsula.

For the next 20 hours, it maneuvered and drifted back and forth in gale-force winds of about 40 miles per hour, according to voyage data provided by MarineTraffic, a maritime analytics provider based in Athens.

“The vessel was sort of in a holding pattern out there because the anchorages in both the U.S. side and the Canadian side of the border are pretty full,” said Laird Hail with the U.S. Coast Guard’s Puget Sound vessel traffic service.

The U.S. Coast Guard reported 16-to-20-foot waves in the area of the Zim Kingston.

Sponsored

“That’s enough to impact a boat pretty badly,” said U.S. Coast Guard Petty Officer 3rd Class Diolanda Caballero.

Canada’s The Weather Network reported a 99 mile per hour gust hitting the ship.

About 12:40 a.m., the Zim Kingston reported losing 40 of its 2,000 shipping containers.

“The ship rolled 35 degrees and, with the height that those containers are on a container ship, it puts a lot of stress on the tie-downs,” Hail said.

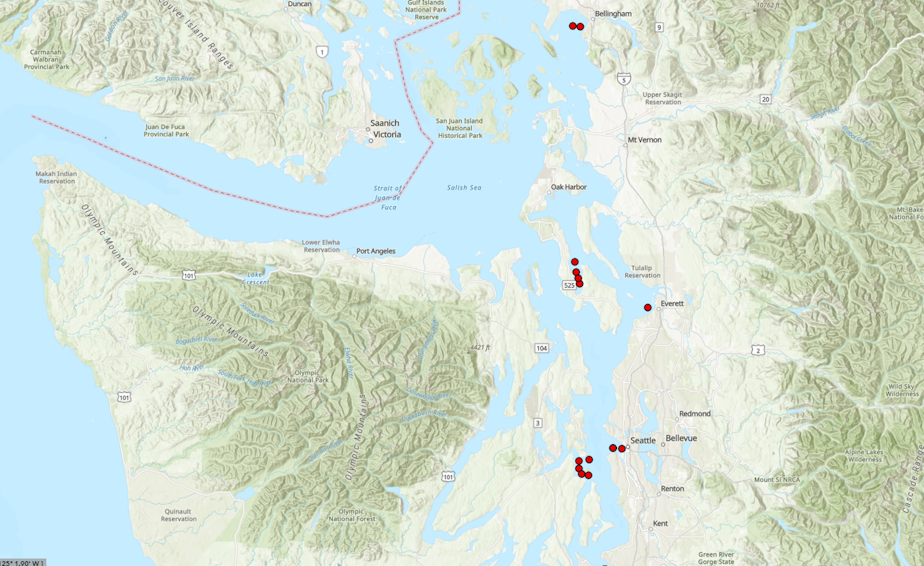

Other big ships at the time had taken refuge inside the sheltered waters of the Salish Sea of Washington and British Columbia. Some occupied anchorages made available for them to ride out the storm. Others, as many as 12 at a time, did laps on a 25-mile-long “racetrack” in the relatively sheltered Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Sponsored

Amid a resurgence of shipping to the West Coast over the past 12 months, ports have been backing up, forcing many ships to wait to offload their goods.

“We've not always had room for vessels to be able to come into anchor, so many of them are holding off shore, waiting for a turn to come into either Canadian waters or US waters to anchor,” Hail said.

It is unclear why the Zim Kingston loitered offshore rather than continue on to safer, more sheltered waters.

“The industry is being encouraged to hold vessels offshore,” Peter Lahay with the International Transport Workers' Federation said in an email from Vancouver.

“In these cases everyone circles the wagons, including regulatory authorities,” Lahay said.

A spokesperson for Danaos Shipping declined to comment.

While west of the Washington coast, the ship’s captain would have communicated with vessel traffic controllers in Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Canadian Coast Guard officials declined to discuss or release those communications.

“We asked Prince Rupert to notify vessels by radio that we would entertain them coming in and doing racetracks,” Hail said.

Bound for the Port of Vancouver, the Zim Kingston would have been most likely to communicate with Canadian officials.

Vancouver Fraser Port Authority spokesperson Matti Polychronis said the Port of Vancouver did not receive any requests for anchorage for the Zim Kingston.

"Transport Canada does not assign anchorages nor did Transport Canada direct the MV Zim Kingston or any other vessel to remain at sea," agency spokesperson Sau Sau Liu said in an email.

“To my knowledge, we did not have to turn away any vessels,” said U.S. Coast Guard sector commander Capt. Patrick Hilbert.

The two nations’ vessel traffic services are like air traffic control at sea, except they lack the authority to order ships into safer locations. They can only make suggestions.

“Not all vessels took us up on those offers,” Hail said. “Some of them elected to stay offshore during the storm.”

In Washington, the Suquamish Tribe has made its traditional waters just north of Bainbridge Island available for anchorage. Only one ship has made use of that location. No big ships have taken up the Port of Seattle’s offer to moor at its Terminal 46, Seattle Port Commission president Fred Felleman said Thursday.

In addition to making sheltered spots available, maritime officials are working to reduce the supply-chain backlogs that are leading some ships to choose to dawdle offshore, even in rough seas.

Mike Moore with the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association said some ships have had to wait up to two weeks—about as long as it takes to cross the Pacific. He said his group has been trying to get information on berth availability at U.S. ports to ships three to four weeks in advance, so they can plan voyages accordingly.

“They could either choose to, say, anchor in China before departure, or they could slow steam”—lower their speed at sea to minimize both waiting time and fuel usage—Moore said.

On Thursday, as another big autumn storm approached the Northwest coast, six container ships were in holding patterns offshore, three were on the Juan de Fuca racetrack, and three were anchored in Puget Sound, according to U.S. Coast Guard officials.

This story has been updated.