He captured footage of a child pepper sprayed during a Seattle protest. Then he was arrested

Evan Hreha of Seattle recorded a video of a young child who had been pepper sprayed during a protest on May 30.

People near Hreha told him that an officer had sprayed the child. Seattle police have denied that the officer accused was responsible for the incident.

A week later, on June 6, he was arrested on suspicion of unlawfully discharging a laser. Hreha, a hairstylist, denies this and maintains that he was never in possession of any laser. He and his attorney say he was wrongfully arrested.

Hreha, 34, was heading home to his apartment in Westlake after spending the evening on Capitol Hill, operating a free hot dog stand with friends.

He needed to feed his 4-year-old greyhound, Ziggy Stardust — a retired race dog he had adopted a week earlier. But he never made it home to her that night.

At about 10:40 p.m., Hreha started to cross the intersection of Belmont Avenue and East Pine Street. That's when multiple Seattle police cruisers suddenly pulled in front of him, blocking his path.

Three officers approached Hreha, he said, and ordered him to put his hands behind his back as they ushered him toward one of the cruisers. Several more cops stood behind nearby to monitor a crowd, including people filming the arrest on their cell phones. Roughly seven police vehicles had descended on the area to make the arrest.

1 min

A group of onlookers confront police about Evan Hreha's arrest on Saturday, June 6, 2020.

1 min

A group of onlookers confront police about Evan Hreha's arrest on Saturday, June 6, 2020.

Hreha said later that he didn't understand why he was being detained.

"They asked me to take my mask and hat off, and they took my picture and sent it to someone for an ID," Hreha told KUOW.

About two minutes later, he said, an officer told him he had been identified as someone who was spotted earlier that night discharging a laser.

Hreha attempted to explain that they must have mistaken him for someone else, he said.

Sponsored

"I was very adamant that, you know, 'You guys can search me — I don't have a laser on me. I've been making hot dogs all night, feeding people for free.'"

The officers didn't seem moved by his clarification, Hreha said. But even as he was handcuffed, searched, and transported to the West Precinct, he felt confident that the mix-up would be sorted out shortly.

"In my mind, I was like, 'Oh, this will be over in a minute once they get the picture back and it's not me.'"

But that moment never arrived. Instead, Hreha was transferred and booked at the King County Jail. At one point, he said, King County jail officers — who are not part of Seattle Police — ignored his miming for help as another man in his holding cell screamed that he was going to kill people.

Hreha, who is gay, worried that this could make him a target in jail.

"When they put me in a holding cell still handcuffed, fear started setting in that perhaps this was in retaliation."

Sponsored

Allegations of police using excessive force against a child

A week before his arrest, on May 30, Hreha had captured the moments after a young child was reportedly pepper sprayed by police amid a peaceful demonstration against racism and police brutality in downtown Seattle.

The video, which has been widely shared online, shows the then 7-year-old boy screaming in agony as milk is poured into his eyes in an effort to relieve the pain. The footage sparked an immense outcry, and was the impetus behind thousands of complaints lodged at the Seattle Police Department that same weekend.

READ: 12,000 complaints filed against Seattle Police after weekend of protests

Attorney James Bible, who is representing the boy's family, said the incident left the boy with chemical burns and has had a lasting emotional impact.

Sponsored

“They felt helpless because there wasn't a whole lot that could be done to stop the pain of what the child was experiencing,” Bible said, adding that no police officers or emergency medical technicians in the area offered assistance.

The incident is currently under review by the Seattle Office of Police Accountability.

Events leading up to the arrest

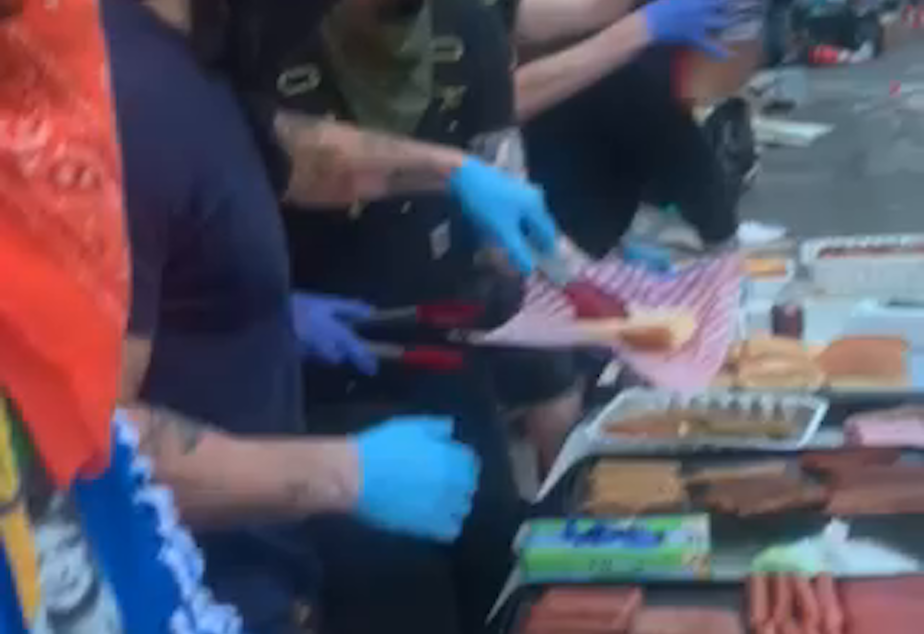

Hreha arrived on Capitol Hill at approximately 7:30 p.m.to help a group of friends operate a hot dog stand on 11th Avenue, in front of Rain City Fit.

Hreha's duties that Saturday evening included slicing and grilling onions for the hot dogs, which were distributed to protesters free of charge.

8 secs

Evan Hreha and a group of friends serve free hot dogs to demonstrators and others on Capitol Hill on Saturday, June 6, 2020.

8 secs

Evan Hreha and a group of friends serve free hot dogs to demonstrators and others on Capitol Hill on Saturday, June 6, 2020.

Hreha decided to call it a night at approximately 10:25 p.m. Then something strange happened, he said.

"When I stepped away from the hot dog stand to say goodbye, I pulled my mask down again to have a cigarette. And that's when a green laser hit my chest — it kind of scanned the people next to me and then stopped on me," he said.

"It was almost like a barcode — the scanner at the grocery store checkout ... it was coming from the rooftop of the building on the corner."

That building was the Richmark Label warehouse, located on East Pine Street between 11th and 12th avenues.

Hreha looked up and saw three people he believed to be police snipers. "They had, you know, the the laser scopes exposed," he said.

A wrongful arrest

Hreha and his attorney, Talitha Hazelton, maintain Hreha was wrongfully arrested and that he was never in possession of, nor did he deploy, any laser.

"It's clear I was wrongfully arrested — I didn't commit a crime," Hreha said. "But was my arrest motivated by a desire for retribution? I don't know."

A spokesperson for the Seattle Police Department declined to comment on Hreha's arrest, citing an ongoing investigation.

As of Thursday afternoon, no charges have been filed against Hreha.

In addition to demanding a 50% funding cut to the Seattle Police Department, local activists have called on officials to release protesters taken into custody, without filing charges.

Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes said in a statement Wednesday that he did not intend to bring criminal charges against peaceful demonstrators.

READ: Why 'defund the police' has become the rallying cry at Seattle protests

Hazelton, however, said there could be lasting consequences for people who find themselves wrongfully arrested — even when no charges are brought against them.

"These will persist on their criminal history searches as an arrest that came up, and they’ll be in the system until a function of time passes," she said. "There's a ripple effect of the permanency of these street level decisions, and the failure of anyone in a position of power to remedy them.”

She added that there's a possibility charges could be filed years down the road, if prosecutors later elect to do so. Unlawfully discharging a laser in Washington state can either be classified as a gross misdemeanor or a class C felony, which carries penalties of up to five years in prison, or up to a $10,000 fine.

Hazelton also called attention to the arresting officers' choice to photograph Hreha's face, which she argues, would be an unreliable way to identify someone from the distance at which police on the rooftop had observed him.

In addition to contesting his arrest, Hreha said he was left without access to four of the five medications he takes — two of which were in a fanny pack he had at the time of his arrest — for the duration of his jail stay. He was there for approximately 43 hours, according to jail records, and was released without bail.

Hreha said the experience of being arrested has left him shaken, but even more understanding of the outrage fueling nationwide demands for greater police accountability.

"I just feel like I have a bit of a target on my back," he said. "But it's nothing compared to what Black people and people of color go through on a daily basis."