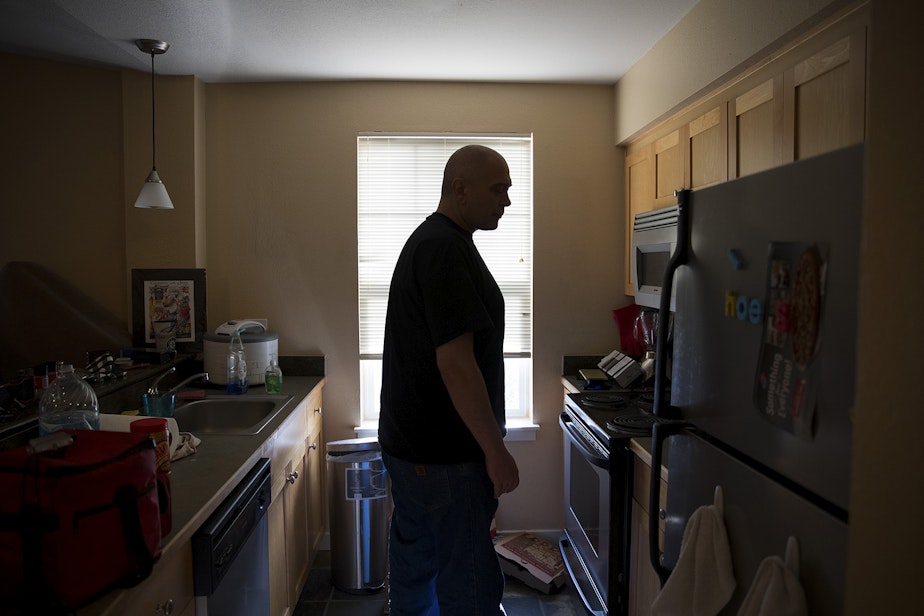

Three years after a fatal shooting, the Jungle has changed and so has this man

Kevin Boggs remembers the shooting in January of 2016.

"I was in a tent about 30 yards away," he said.

It took place one night in what was once the Jungle, an unauthorized homeless encampment under Interstate 5. Five people were shot and two of them died.

Three brothers, aged 13, 16 and 17 at the time, were charged with the shootings. Police records indicate the crime may have been related to a drug deal turned ugly.

For politicians, the shooting became a call to action: It spurred city officials to swiftly issue a mandate that the camp, home to roughly 400 homeless people, be shut down.

This put the city at odds with activists who argued the area shouldn't be cleared until there was somewhere else for people to go.

It took months, but eventually the Jungle was cleared, and many people who had been living there scattered – landing elsewhere on the city's streets.

Sponsored

Three years on, Kevin Boggs is no longer one of them.

Boggs said he slept through the gunfire that night because the Jungle was often that loud from the sound of the freeway.

Instead, he awoke to flashing red and blue lights. It was a wake-up call.

"Every now and then you just have this snap back to reality and you go, 'I need to get out of here,'” he said. “That was one of those nights.”

Boggs used to be a glassblower. He lost his job when the economy crashed and decided to go back to university. He started using drugs. Eventually, heroin drove him to the streets, first to Lake City, then to the Jungle.

Sponsored

Boggs said he initially moved to the Jungle because there was a sense of security there. On the streets of Lake City, Boggs' tent kept getting ransacked, he said. But in the Jungle, there were unofficial guards and lookouts — and strangers weren’t welcome.

And it was in the Jungle that Boggs tried to get clean. He had kicked heroin and was going to a nearby methadone clinic for treatment.

But Boggs said he still used other drugs intermittently, which was easy because they were so readily available.

“When I’m living in a tent, I’m living next door to both drug dealers and users that enable me to just get drugs on my way home,” Boggs said. “If you go to ask for a cup of sugar from the guy next door and he’s smoking a crack pipe you’re in trouble.”

Boggs said it wasn’t until he left the Jungle that he was able to truly get sober.

Sponsored

After the shooting, notices went up telling people to vacate and the months-long process of doing outreach and clearing the site began. Boggs decided to leave for another encampment.

He eventually ended up in drug court after he was arrested for a crime he'd committed while high. He said that program is the reason he got off the streets.

"It's a program that works and it's because of the accountability attached to it,” he said. “If you get high again while you're in the program they discipline you. And you can give up but then you'd have a felony on your record."

Of the people who have entered into King County's drug court program over the past five years, about 60 percent have graduated, representing more than 600 dismissed felony cases, according to a spokesperson for the program.

A county study indicates at an 18-month follow-up after drug court enrollment, 88 percent of participants had no new felony convictions and 71 percent had no new convictions for any crime.

Sponsored

But drug court doesn't work for everyone. As an abstinence-based program, continued drug use, or someone not wanting to participate in the recommended level of treatment, are common challenges that lead to people not graduating.

But Boggs said the rigidity was good for him.

Boggs said he graduated from the course, got training as a welder and got a job at a local shipyard.

These days, life is slowly returning to normal.

"Well, it's back to where it was long before my fall, my slow spiral,” he said. “I grew up having a regular life, you know, people aren't born drug addicts."

He has an apartment now, a car and a cat named Jasmine. He’s in touch with his family and looking forward to his brother’s wedding in May.

Three years after the shooting, the Jungle looks different, too. In 2016, Jeff Lilley with the Union Gospel Mission told Seattle City Council members that their outreach workers contacted 357 people in the Jungle multiple times over several months.

Of those contacted, fewer than 100 accepted offers of service, according to Lilley. Overall, only a fraction ended up sheltered. And these days, only a handful of tents appear to occupy the area that used to house hundreds.

Service providers say some people go under there to sleep at night, but they pack up early and move on.

The whole area has now been designated an emphasis zone by the city, meaning it is patrolled by Seattle police and people can be moved out without notice.

Seattle's overall homelessness services system has also seen changes since 2016.

More people are getting help, but the issue of homelessness remains at crisis levels three years after the shooting.

As for Kevin Boggs, his journey out of the jungle is ongoing. He hopes to help others by becoming a recovery coach.