Washington state's high point has a national park. Its low point doesn’t have a name

Thousands climb Mount Rainier, the highest point in Washington, every year. But no one, apparently, has ever been to the state’s lowest point.

While the 14,410-foot volcano is a regional icon and, since 1899, a national park, the low point doesn’t even have a name.

The unnamed, unvisited, and mostly unknown spot is so far underwater that no light penetrates. It’s far too deep for scuba divers, too deep even for the underwater robots used by the state to keep tabs on its deepest denizens, from rockfish to octopus to corals.

“It's not devoid of life by any stretch,” said biologist Bob Pacunski. He runs the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s remotely operated vehicle program.

“I would dare say my group has seen more of the bottom of Puget Sound than any other group of humans alive, and/or dead,” Pacunski said.

But the state’s remotely operated vehicles can only go down to the end of their thousand-foot tether. That means the deepest parts of Washington, including its nameless nadir, remain unexplored.

Sponsored

Call it the Salish Trench. The San Juan Mystery Spot? The Anti-Rainier? Or maybe Deepy McDeepface?

“Yeah, it's pretty cool. There are still plenty of undiscovered places out there,” Pacunski said. “We find cool stuff with ROV all the time, stuff we’re not even looking for.”

How low can you go?

Stuart Island, the westernmost of Washington’s San Juan Islands, isn’t especially rugged. Its rounded high point, known as Tip Top Hill, only rises about 600 feet above sea level.

Sponsored

But about a mile off the island’s western tip lies a geographic extreme, a state superlative. In a glacial gouge some 1,140 feet below the surface, in the permanent night of the deep, sits the lowest spot in Washington state.

From that spot, it would take nearly two Space Needles to reach the surface.

If you plunked Seattle’s 76-story Columbia Center, the tallest skyscraper in the Pacific Northwest, down there, the cocktail-sipping members of the Columbia Tower Club on its top floor would still be more than 100 feet underwater.

Cargo ships and oil tankers pass overhead all the time, but these inkiest of depths have apparently never had a human visitor.

Even commercial trawlers don’t fish that deep.

Sponsored

“That's a lot of work to go fish those depths,” Pacunski said. “It's just not worth the time and energy to do it.”

Military and research submarines can dive much deeper, but as far as Bob Pacunski knows, no one has gone to the very deepest part of Washington.

Washington's nautical nadir sits about two very dark, very wet football fields away from the invisible border with Canada, and the deep glacial gouge it sits in straddles the border. Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans officials said their researchers had sent no remotely operated vehicles near the bottom of the gouge.

Elsewhere, pre-nuclear-era submarines would sometimes rest on the seafloor to save their batteries but, according to military news site SOFREP, they did so in waters less than 500 feet deep.

Nuclear subs today have little need to hit rock bottom, which would risk damaging the rubbery stealth coating and sensors on their undersides and fouling their water-intake openings with sediment.

Sponsored

“We are unaware of any Navy assets attempting to reach that particular spot,” U.S. Navy Region Northwest spokesperson Julianne Leinenveber said by email.

“This would be a very difficult place to dive as the tidal currents here are very strong and a submersible would not be able to keep station [hover in place] for more than a few minutes during slack tides,” said Gary Greene, a geologist with Moss Landing Marine Labs, in an email.

The only government designation for the spot where the waters of Haro Strait, Boundary Pass, and Prevost Passage collide is the "Turn Point Special Operating Area." It’s where oil tankers and cargo ships make a sharp turn to stay on the shipping route between the Port of Vancouver and the rest of the world. They are expected to keep at least half a mile between them and any other big ships there.

Sponsored

Just because the depths are unvisited and unseen doesn’t mean they’re completely unknown.

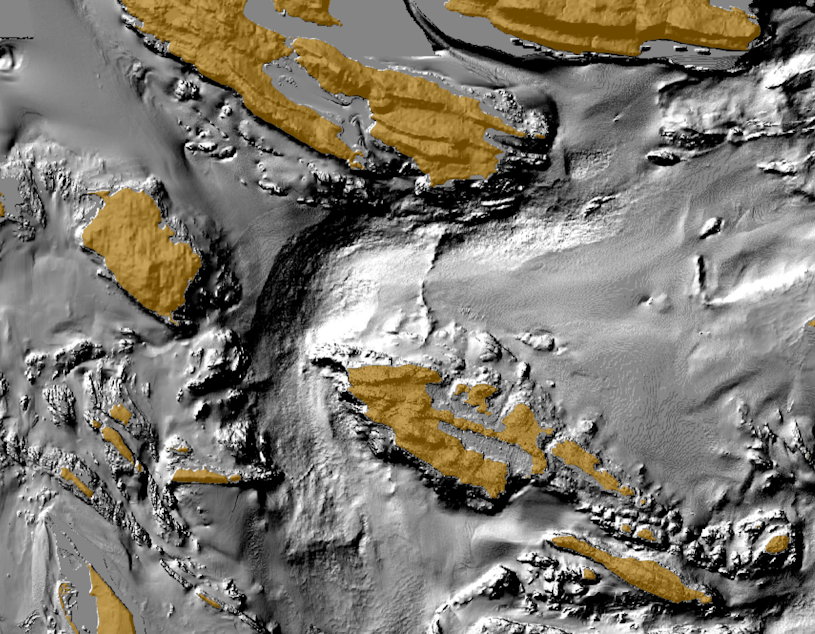

Sophisticated multibeam sonar devices attached to research vessels have mapped the topography far below the sea surface. Sound bouncing in different ways off mud or rock has enabled topside researchers to identify the types of bottom habitat and the species likely to be found there.

“From our investigation the bottom here consists of boulders, cobbles, pebbles, and gravels with sand and finer grain sediments swept away from the strong bottom currents,” Greene said by email. “It is a pretty hostile area.”

While photographs and drawings of Mount Rainier adorn everything from postcards to coffee mugs, no photographs are known to exist of the glacier-capped volcano’s glacier-gouged opposite.

A 3-D map produced from sonar is the closest thing available.

The weight of a mile-high advancing ice sheet originally scoured the deep trough that curves around the northwest tip of Stuart Island. Powerful tidal currents sweeping through the area day in and day out keep it from filling up with sediment.

Honorable mentions

If you ignore political boundaries, this unnamed spot becomes less than superlative. With Washington state’s jurisdiction extending up to 3 nautical miles from the coast, the Salish Trench, let’s call it, reaches the farthest below sea level in state waters. But the Juan de Fuca, Quinault, and other Pacific Ocean canyons quickly head to much greater depths just outside the state’s official three-mile limits.

The deepest spot within the Salish Sea — the inland sea shared by British Columbia and Washington — lies about 85 miles north of Stuart Island. The dramatic fjord of Jervis Inlet wriggles its way out of British Columbia’s Coast Mountains, its waters reaching a maximum depth of 2,224 feet — about twice as deep as most of the Salish Sea, according to the Canadian Hydrographic Service— just before a shallower pile of glacier-deposited debris at its mouth.

In addition, there is one spot in Washington state proper that is farther underwater than the Salish Trench. Snaking through the eastern edge of the North Cascades, Lake Chelan follows a winding path carved by prehistoric ice sheets. At 1,486 feet from whitecaps to permanently dark lakebed, Lake Chelan is deeper than Puget Sound. But with its waves glinting in the sunshine at 1,100 feet elevation, the glacier-gouged lake's deepest point is a mere 386 feet below sea level.

Other exceptionally profound spots of Puget Sound include a glacial scour between Boeing Creek in Shoreline and Point Jefferson on the Kitsap Peninsula and one between Seattle’s Shilshole Bay and Bainbridge Island. Both bottom out at more than 900 feet deep.