The grim 'family tree' of gun violence in King County

Lamaria Pope can tick off a dozen names of people she knows who have been killed by guns ... in the last four years.

“The numbers go up man, every two weeks,” said Pope, who is 21. “My cousin Herman, Junior, Isaiah, Shay, Robert.”

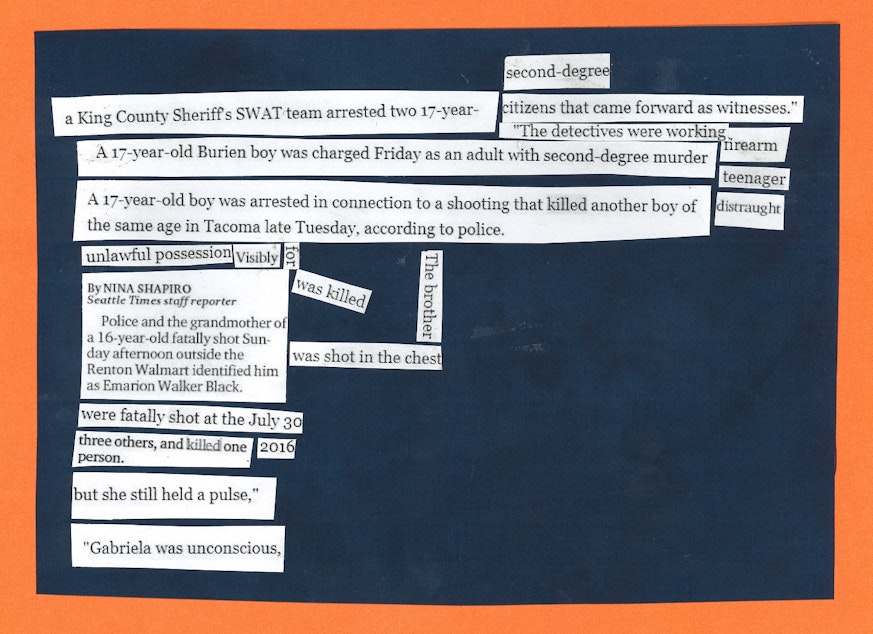

This is what researchers call the "family tree" of gun violence: People who have experienced it first hand – even as a witness or victim – tend to be connected socially.

For the first time, King County is taking a fresh look at crime data to see who is in this grim social network ... to find ways to stop it from growing.

At an intersection in Rainier Valley, Pope stared out her car window. Outside, rain pelted a deflated mylar balloon tied to a small memorial.

For Pope, this street corner illustrates the ripple effect of gun violence. This is where her best friend Junior was shot and killed four years ago by another teenager on New Year's Eve.

Sponsored

Pope’s loss was compounded shortly after, when Junior’s younger brother got a gun and used it to kill himself.

“It influenced his decision making," Pope said. "He got the gun because his brother was killed. And then he didn’t go retaliate, he just took his self. So it plays a part."

Pope said she has become immune to the violence. Losing someone to a gun has become a lifestyle for her. But science says Pope is not immune. And if left unaddressed, the trauma that has enveloped her and her peer group will likely point many of them into the criminal justice system.

The King County Prosecutor's office is trying a new approach by using data to reach people like Pope early.

Prosecutor Karissa Taylor said law enforcement already has advocates for domestic violence and special assault, but not for these cases.

Sponsored

“No one is really reaching out to these victims and saying you were shot; how can we help you and your family?" Taylor said.

To find the people they need to reach, Taylor's office is taking a deeper look at arrest and gunshot data from eight law enforcement agencies. From there, a network of victims, witnesses and suspects emerges.

What they've learned wouldn't surprise Pope or her peers.

In 2017, 83 percent of victims were male and people of color. Nearly half were younger than 25.

Taylor said this work will be complicated. A historical distrust of law enforcement by the people in this network also puts her office at a disadvantage.

Sponsored

So Taylor wants to give this information to community partners who can mentor these young people and steer them to better choices. That could mean counseling or help with medical expenses or even the light bill.

“If we can keep them free from even getting on the criminal justice radar that would be a win," Taylor said.

Back in the Rainier Valley, Lamaria Pope isn’t sure how her friends would react to being approached after a shooting.

While Pope said she would never carry a weapon, she said people she knows equate guns with power. The problems being solved with guns are about adolescent issues like girls and money.

“It’s so easy for us to get guns," she said. "It’s easier for us to pull the trigger with no resentment."

Sponsored

Pope believes it's going to take a lot of trust-building and work by the prosecutor's office for Karissa Taylor’s effort to gain traction in her circles. Even with community mentors.

“You gotta know it's not going to be documented," Pope said. "It's not going to be used against you; you're not going to court."

But Pope can also remember a time when someone stepped in. It was after her classmate Robert was shot and killed before graduation.

“Everybody wanted to give up," Pope said. "I didn't want to go back to school because it just didn't make sense. It is like, this is haunting us."

That same week, counselors came in to help students talk about what happened.

Sponsored

At first Pope was resistant, but something changed her mind.

“It really helped," she said. "It helped us get through the rest of the week. And the school year alone. I wouldn't go act off of emotion because I was able to talk about my emotion and talk about the anger that I was feeling. So therefore I could try to strategize and think differently and move differently.”

That was enough for that day and that week. But not long term.

Last year Pope was arrested and charged with a felony.

Karissa Taylor believes there could have been a different outcome if mentors had been in place.

Pope agrees.

“Maybe there could be some type of organization set up," she said, "from elementary, to middle schools, to high schools or even colleges. There's some type of counseling, some type of something, where you could just get certain things off your chest."