Seattle's Hobson Place offers a fresh start after homelessness. For some, it's a brutal journey

Catherine goes to see her son C.J. every couple days. Often he's standing outside his apartment in Hobson Place, just watching for her. He gets in the car and she takes him for a drive, to buy him hot food and cigarettes. But he talks to himself, not answering her questions or making conversation. She worries that he's slipping away, and she can't seem to get anyone's attention.

(We’re not using full names in this story because Catherine fears it could make her son’s situation worse.)

Catherine said C.J., who is in his late 20s, has not had an easy life. In the last several years, he was injured in a shooting and diagnosed with schizophrenia. When Catherine learned that C.J. could go from living on the streets to his own apartment, she was thrilled.

She helped him move into the modern blue and gray building known as Hobson Place in Rainier Valley. It's one of the city's largest permanent supportive housing projects for formerly homeless people. The 177-unit building, with a medical clinic on the ground floor, opened to much fanfare in January 2022. There was even a virtual ribbon cutting. C.J. moved in soon after.

“I was very happy that that happened,” she said, “knowing they were going to have mental health services, a clinic, and the housing itself.”

Sponsored

She took pleasure in setting C.J. up with a television, microwave, and everything he needed to feel at home.

For several months things went well for him at Hobson Place. But then, she said, C.J. stopped taking his medication and traded all of his possessions for methamphetamine.

“All his stuff disappeared in his apartment,” she said, “everything, down to he had no shoes on, and it was a very sad sight.”

She blamed the people supplying him with illicit drugs inside and outside the building. And she said her calls and letters to the staff asking them to take action have gotten no response.

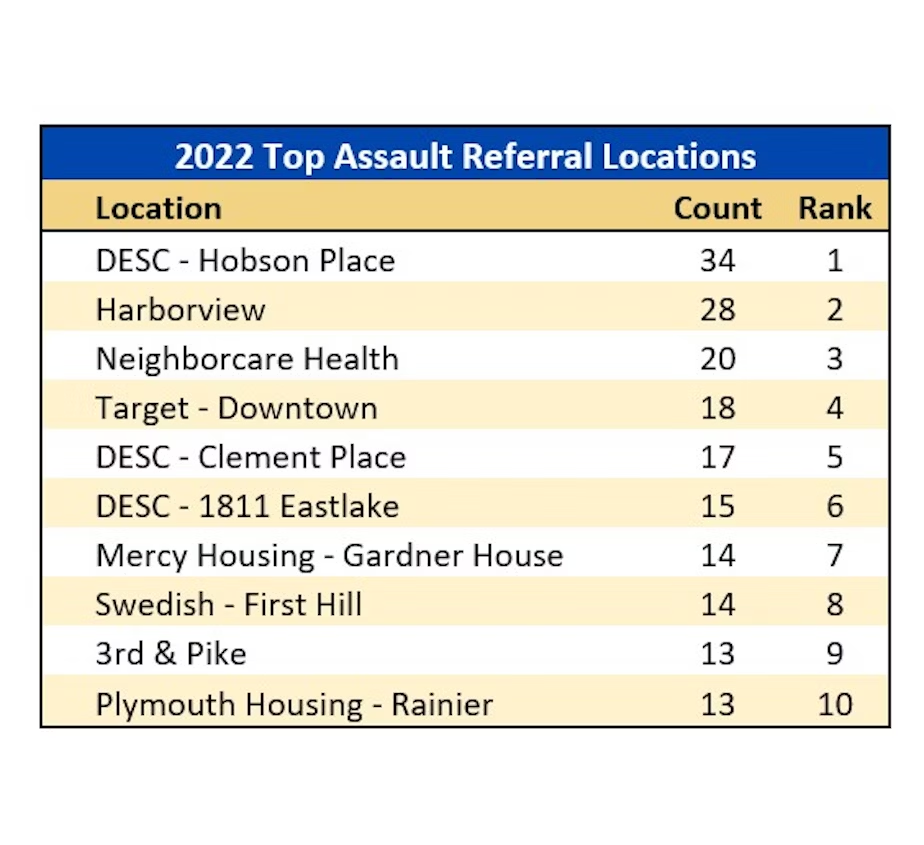

Hobson Place's first year has been tumultuous for other residents too, as well as for some of its staff. According to the Seattle City Attorney’s Office, there were 34 misdemeanor assault cases at Hobson Place in 2022, the most of any single address in the city that year.

Sponsored

Research indicates that supportive housing facilities like Hobson Place are effective at preventing homelessness. But experts say the problems of violence and substance use show the need for more effective interventions as people make that transition.

The nonprofit Downtown Emergency Service Center manages more than 1,300 units of permanent supportive housing throughout Seattle, including Hobson Place. DESC says bringing people out of the chaos of homelessness gives those who struggle with mental illness or drug dependency a platform for recovery. This “housing first” approach was pioneered by DESC’s former director Bill Hobson, the namesake of the building where Catherine's son C.J. now lives.

Catherine said she’d like to see more staff monitoring the wellbeing of residents, and checking on them in their rooms.

She described during one visit seeing blood in his hallway, which she reported to staff.

Sponsored

“All through the hallway there was blood," Catherine recalled. "It horrified me, thinking oh my God, somebody’s hurt.”

She said the next day it was still there.

She also described entering the elevator as a man inside was about to inject heroin.

And she said her son's condition is worsening. This winter he told her he was outside the entrance to Hobson Place all night because he lost his key.

At another point this spring, C.J. tried to walk out into traffic on busy Rainier Avenue. Staff came out to intervene, but to her chagrin did not call 911.

Sponsored

She said that was a crucial opportunity to seek help for him. Catherine obtained a court order to have him hospitalized after that and sent to drug treatment, but he was released two weeks later. Catherine said the presence of drugs is harming residents like her son.

“I don’t agree with [allowing drugs] in mentally ill housing,” she said. “If that was out of there and they got their proper meds, security, rules enforced — I think it would be a better place to live.”

Noah Fay, senior housing director at the DESC, said the nonprofit is constantly trying to strike a balance between giving residents their legal rights as tenants while offering them case management and other help.

“I wouldn’t say it’s fair to say substance use is simply allowed or tolerated,” Fay said. “However, we don’t see it as a lease enforcement issue inherently. We see it as an underlying challenge that our clients are living with, and we want to provide support to them while ensuring they have a safe place to live.”

He said he can’t discuss specific clients, but C.J.’s struggles at Hobson Place don’t appear to be unusual.

Sponsored

“We definitely have had examples of people giving away their stuff or selling their stuff," Fay said. "If they’re enmeshed in pretty significant addiction, it is not uncommon for people to not hold on to their possessions very long.”

Fay said if someone feels taken advantage of, staff can help them report those losses to law enforcement. At the same time, he said Hobson Place residents are tenants with the right to make their own decisions.

He said DESC would not tolerate someone actively dealing drugs in the building, and has evicted people in rare cases.

“Some people will facilitate to support their own use. We’re not simply okay with that,” he said, but “we will try to find solutions that don’t impact the community, we’ll work with people individually.”

Crisis intervention "broken"

Fay and Catherine are in agreement about one thing — the system to evaluate and hospitalize people when they’re in severe crisis is broken. Catherine is still seeking to have C.J. hospitalized. She said he’s been hearing voices and opening all the water faucets in his room.

Fay said over the last several years, designated crisis responders have shown up more slowly or not at all.

“We intentionally work with people here who are dealing with some of the more profound and significant behavioral health conditions, meaning we need the crisis system to work,” he explained.

Fay said people just coming out of homelessness face intense behavioral challenges, which contributed to the high number of assaults as Hobson Place opened in 2022. He said assaults have significantly decreased so far this year. But some of those assaults were against building staff.

“The people left holding the proverbial bag of trying to support people through acute crisis are DESC permanent supportive housing staff who have done a heroic job, but have also bore the brunt, and that does not weigh lightly on me,” he said.

After "housing first," what next?

In a review of existing studies, the medical journal "The Lancet" found that permanent supportive housing successfully reduced homelessness, but has demonstrated no impact, good or bad, on residents’ mental health or substance use.

Academic researchers are looking at ways to improve those outcomes and promote social integration for formerly homeless people.

“It’s hard to stop an addiction, and just because you’re housed doesn’t mean that immediately goes away,” said Jack Tsai, research director for National Center on Homelessness among Veterans and a professor of public health at the University of Texas. “Some of the loneliness and the new surroundings, that may not help the situation.”

Tsai said creating ways for these residents to support each other — like group case management instead of one-on-one — seems to show promise. He designed a program like that for the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“And we found that really effective, because lots of homeless folks and formerly homeless folks love helping each other out,” he said.

At Washington State University’s Department of Community and Behavioral Health, Assistant Professor Liat Kriegel is looking at how to help people in permanent supportive housing build community ties. She said even if people are engaged in treatment for behavioral health disorders, that’s only a small fraction of their time each day.

“You have another part of your life that you’re living, and that part has to be not just sustainable but enjoyable,” she said.

Kriegel’s colleague, WSU Professor Michael McDonell, is piloting a program — in Seattle and elsewhere — to reward people in permanent supportive housing with gift cards and other prizes for not using drugs.

“We’ve got to do better — we’ve just got to out-hustle the drug dealers,” McDonell said. That could be by “repeatedly offering interventions and repeatedly offering choices,” all while keeping people housed, he said.

Catherine said C.J. used to enjoy family gatherings when he was on his medication, but these days his behavior is too erratic. She said she’s losing hope that any intervention will come in time to help him.