Common cancer screening methods are less accurate for Black women. This UW doctor has made it her mission to change that

Endometrial cancer is one of the most common cancers in the United States, and cases are increasing each year. But a new concern is that common cancer screening methods are not catching cases in Black women. According to a new study from the University of Washington, a screening is four times less likely to be accurate for Black women than white women.

Dr. Kemi Doll is a gynecologic oncologist with UW's School of Medicine, and the lead researcher on the study. She told KUOW’s Paige Browning about her findings.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Paige Browning: First, can you just go through what are the symptoms of endometrial cancer, and how is it commonly treated?

Dr. Kemi Doll: Yes. The average age of diagnosis of endometrial cancer is a woman in her 60s. The primary symptom of endometrial cancer is that after a woman has gone through menopause, which most women will have gone through in their 60s, she starts having vaginal bleeding again. We call that post-menopausal bleeding. That is the primary symptom of endometrial cancer by far. Over 90% of women with endometrial cancer will have that bleeding.

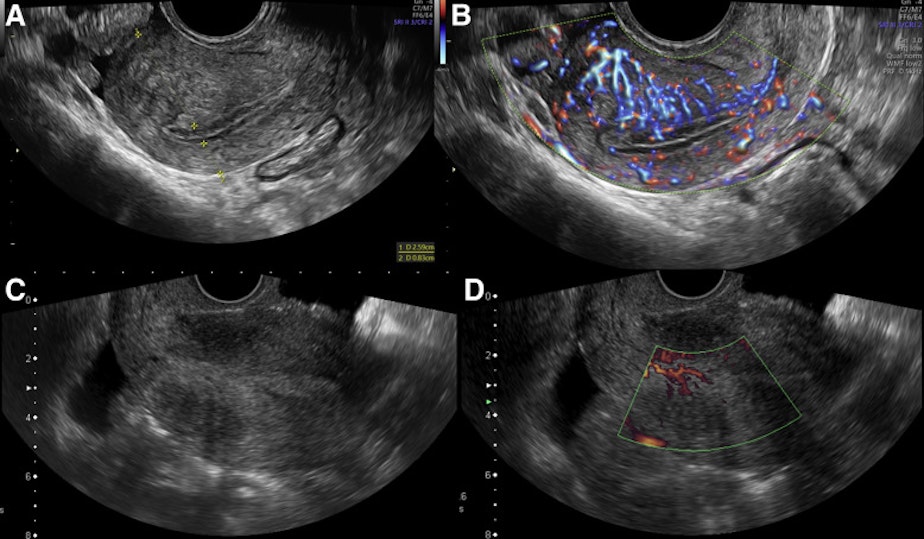

The way that we are able to detect it is that a woman has bleeding like this, and then we do what's called a transvaginal ultrasound, and we are able to measure the thickness of the lining of the uterus. That gives us an impression of whether or not the bleeding is coming from thickened tissue that could represent endometrial cancer. That measurement then helps us decide whether or not a woman then needs a biopsy in order to confirm if the tissue was cancerous or not.

That is how it's supposed to go. The problem though, is that that ultrasound screening test is not as accurate for Black women because of some different characteristics that Black women have coming in if they have bleeding.

Sponsored

I read that the mortality rate for this cancer for Black women is over 90% higher than for white women. That's just an astounding disparity. Why is that?

One of the reasons why is that Black women are diagnosed with what we call later stage, or more advanced cancer. So by the time Black women are diagnosed and know that they have a cancer, they're more often going to be in stage three or four, which has a lower survival in terms of treatment.

Another reason is that not all endometrial cancers are the same. There are some types that are more aggressive than others. Black women are more likely to be diagnosed, and have these more aggressive types. These types really need to be caught early in order to increase the chance of survival as well.

Lastly, health and survival are not just about biology. Because of the other issues like access to care, being able to receive the right quality of treatment for the cancer, these things are also less likely to happen for Black women. When we add all of those things up together, that's how we get to such a marked and stark disparity.

So the screening itself is not particularly geared toward Black women. Is this an issue of inequity? How do you see it?

Sponsored

Thank you for asking. What I would say is that the screening tool itself, using ultrasound to decide whether or not to do a biopsy, comes from the idea that we really don't want to do inappropriate tests. We don't want to subject women to biopsy if they don't need it.

The problem is that the data that this approach is based on was data that didn't include Black women. The reason why that matters is that Black women are much more likely to have fibroids that distort the measurement on ultrasound, and so it's not as accurate. Then, Black women are more likely to have the kind of endometrial cancers that don't cause a thickness that we measure on ultrasound.

So, when we're using data that didn't include Black women, that's how we end up with a strategy that works for some, but it doesn't work for everybody. So I would absolutely call that an inequity, because when we do research that isn't inclusive, and that didn't include Black women from the beginning, we end up with inequity in our literal delivery of care, in how we've designed care.

In your research, did the results surprise you?

Yes and no. I guessed that we would find some difference in accuracy, because of what we know about ultrasound and how it works and the influences. I didn't know it would be as strong as it was. That was important. it's an important finding, but also it was helpful, because oftentimes in disparities, we think we know all of the factors. When we think we've controlled all of the factors, and we still see that a group of women, like Black women, aren't doing as well, it can be very frustrating to try to understand well, why is this?

Sponsored

When we find out things that add to information, and that can help bridge those gaps, it can be surprising, it can be frustrating, but ultimately for me it also is hopeful, because now I know how we can move forward, adjust things, and improve them so that we close that gap.

So we know that Black women have a higher risk of this cancer. How should they approach care and treatment?

The first thing is awareness. I want Black women to know that, one, endometrial cancer exists, and two, to simply know the signs. If they are finished with menopause and they start bleeding again, that is a reason to go in for evaluations.

The second thing I want them to know is that having a clear and full explanation is something they absolutely deserve. Because we know that what happens often with reproductive symptoms among Black women is that if they're tolerable, they may not push for an explanation.

I want Black women to know that it's okay to want to know what's going on with their body. And especially in the case of postmenopausal bleeding, there should be a diagnosis. It doesn't mean that you have endometrial cancer, but you should have clarity about whether it's there or not.

Sponsored

In terms of approaching treatment, I want Black women with endometrial cancer; who may be facing that diagnosis, or who may be worried that that's what's going on, I want them to know that we have effective treatments, and they are most effective the earlier someone is diagnosed.

How did you come to be involved in the study? Why did you get involved?

I'm a Black woman myself, and I remember being in training for gynecologic oncology, and learning about endometrial cancer, learning how to take care of it, learning just as a fact that Black women are more likely to get aggressive disease, and Black women are more likely to die, just simply stated as a fact.

I remember when I was learning about that wondering why, and ultimately not wanting that to be the end of the story. Because when I read those statistics, and I thought about those women in their 60s, that's my mom, those are my aunts, that's going to be me.

It was really important for me to not have that be one line in a textbook with no further explanation, but to approach these questions as something that we can do something about. This study is part of my larger career. The goal of it is really to not just narrow but to eliminate this mortality disparity in endometrial cancer among Black women.

Sponsored

In addition to research, I do advocacy. I co-founded EKANA, the Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African Americans. That is an organization that is intended to address lot of the things we spoke about, really increasing awareness, stopping the silencing around bleeding as a symptom, talking about ultrasound, biopsies, treatment, and really developing a community of support around Black women who are affected by this disease.

Where will you direct your research next?

Right now, we're doing research to develop a new algorithm that may still incorporate transvaginal ultrasound, but in a way that will not miss cancers among Black women. We're moving forward with that research so our guidelines are more effective for Black women, in addition to other work providing social support, and improving treatment adherence for Black women, ultimately, all directed at improving survival.

Listen to an extended version of Paige Browning’s interview with Dr. Kemi Doll below.