We need to think about the ethics of true crime

People seem to love crime content. Crime-related media has become a huge part of popular culture. But is it ethical?

RadioActive's Alayna Ly, Morgen White, and Colin Yuen talked to listeners, creators, and media ethicists to find out.

[RadioActive Youth Media is KUOW's radio journalism and audio storytelling program for young people. This story was entirely youth-produced, from the writing to the audio editing.]

Podcast transcript:

Morgen White: People seem to love crime content. Crime-related media has become a huge part of popular culture. In 2021, "Criminal Minds" was the most viewed TV show in the U.S.

["Criminal Minds" TV show clip: "I’ll explain when I see you, I’ll meet you in a half-hour. What’s going on? D.C. may have a serial killer; I think I just let him get away."]

Sponsored

Morgen: In that same year, three out of the top 10 streamed podcasts in the U.S. belonged to the true-crime genre. One of them was "Crime Junkie."

["Crime Junkie" podcast clip: "So if you can’t get enough true crime, congratulations, cause you just found your people."]

Morgen: Another, "My Favorite Murder."

["My Favorite Murder" podcast clip: "I’m Karen. I’m Georgia. And we love murder. We love murder. We don’t want to get murdered. We love true crime."]

Morgen: And last but not least, "Serial."

Sponsored

["Serial" podcast clip: "From This American Life and WBEZ Chicago, it’s "Serial," one story told week by week. I’m Sarah Koenig."]

Morgen: And I’m Morgen White.

And this is a RadioActive podcast. RadioActive is a program where youth come together and produce great radio at KUOW Public Radio in Seattle.

True crime is a nonfiction genre where a creator examines a crime that has happened or is ongoing. My team and I wanted to dive into this genre because we’re interested in its ethical aspects.

Section 1: The Listeners

Sponsored

Morgen: Our first step was to talk to listeners. Our reporter Colin Yuen went out with his recorder in hand to see what folks were thinking and feeling about this topic.

Hey, Colin.

Colin Yuen: Hey, Morgen!

Morgen: What did you find?

Colin: Well, I got a variety of different answers. But the first thing I wanted to figure out was, what is it about true crime that is so appealing?

Owen Sykes: I think it provides the kind of details that you wouldn’t otherwise get from normal news reports.

Sponsored

Redah Baig: Honestly I just like learning about the certain murders or, like, mysteries of the people that went missing.

Sara Cizek: I find it relaxing, I also like learning about like why they murdered the people, and this is going to sound really bad, but, like, how?

Colin: From what I heard, it's definitely no mystery why true crime has risen to fame. But sometimes, it feels kinda weird, especially when talking about people who died in terrible situations.

So I also decided to ask those same people if they had thought about the ethics of true crime as well.

Kody Shabaga: I haven't really thought too much about the ethics, but I guess the victim probably wouldn't like it.

Owen: Yeah, it's genuinely just something I haven’t put a lot of thought into. But I think I probably should from now on.

Sponsored

Sara: Yeah, kind of. I mean really, like, really slightly. Like, at a minimum.

Colin: That was Kody Shabaga, Owen Sykes, Redah Baig, and Sara Cizek, students at Issaquah High School.

After talking to people about the ethics of true crime, it seems that people hadn’t really been thinking about it as much as they were listening to it.

It kinda left me wondering: Is there an ethical way to listen to – or even to create – true crime?

Morgen: Yeah! That's a great question, Colin.

But it’s clear that true crime is here to stay. But we want to approach the topic of conscientious listening and creating.

Section 2: The Creators

Morgen: To get an inside look at the production, I reached out to a few true-crime podcast creators.

I wanted to discuss the ethical problems that may show up when creating this content. So I decided to talk to Matt Shaer.

He and his co-reporter Eric Benson started the podcast "Suspect." It follows the murder of Arpana Jinaga in 2008. She was a kind, 24-year-old Indian American woman who immigrated to the United States.

The podcast focuses on Emmanuel Fair, who was a young man unsure of his path in life. At the party where Arpina was murdered, he was the only Black person present, and the police settled on him as their main suspect.

Matt Shaer: But just the fact that [Emanual]was willing to share so much of this part of his life that had been so incredibly painful made it impossible not to get emotionally invested in it, right, because someone is literally talking about the worst part of their life for hours on end.

Morgen: One of the critiques of true crime though has been its entertainment factor. True crime is inherently focused on the tragedies of another human being.

I asked Matt how he felt about making a true-crime podcast that would be consumed as entertainment.

Matt Shaer: I feel like in my most optimistic sense, I wouldn't want people to consume it as entertainment, or as "true crime." I would want people to experience it as a documentary about the criminal justice system. However, I know that that's not how people listen to podcasts.

Morgen: Another critique of the genre is how we focus on the perpetrator. And how the victim is often lost in the story. Here’s Matt again.

Matt Shaer: Often there's a real focus on glamorizing the perpetrator and not talking about who the victim was as a person , which is just an oversight on so many levels. It robs people of a connection to another human being. It puts their focus on the wrong person or the wrong people. And it's just not a good way of storytelling.

Morgen: Matt made it clear that he intended his podcast to not only share the life of Arpina, but also bring light to the inequity of Emmanuel’s treatment.

I didn’t want to just talk to creators, though. I also wanted to talk to victims' families.

This is how one loved one did it, David Kushner.

David Kushner (on his podcast, "Alligator Candy"): Reliving my family's story for this podcast has not been easy. The loss and trauma and grief, that stuff never goes away. But I hope sharing my story can in some small way help other people.

Morgen: David is a journalist, and in his podcast, "Alligator Candy," he tells the story of his brother’s murder, and how it affected their family.

David explained that there were two sides. His journalist side, and the side that had experienced it.

David: You know, my purpose was really, really kind of as a journalist, to like say, you know, here's something we hear about a lot and people are fascinated by it, but you know, we don't really hear about it very often from the inside. And so that's what I tried to do.

Morgen (on tape): Do you think that genre in general, exploits victims and their families?

David: Yes. Because I mean, I saw that firsthand. I experienced that firsthand. I still do. I know that almost as a reporter too, that that's a fact. And we see that again and again. So yeah, I think there's a real problem with the lack of empathy for victims in general.

Morgen: After talking to true-crime creators who seemed to make their podcasts for awareness, and healing purposes, I wanted to dig deeper into the ethics. So, I went back to my team, and we started talking.

Section 3: Media Ethics

Morgen: We wanted to answer the big question: Is true crime ethical? Well… it’s neither a yes nor a no. Tt’s a spectrum, with a whole lot of gray in the middle.

Ultimately, no one can dictate what media you consume or create. But there are ways you can be more intentional with your decisions.

I decided to talk to our research reporter, Alayna, to see what she had found. Hey, Alayna.

Alayna Ly: Hey, Morgen!

Morgen: What did you find during your research?

Alayna: I spoke to Subbu Vincent, the director of journalism and media ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

He talked about how it’s important for true-crime creators to explain how their content was made. Essentially, being transparent with the audience and everyone involved. Disclosures should include information…

Subbu Vincent: ...that has to do with everything that the content creators have to say about where they got the material from, why they decided to actually do it, and whether they’re making any disclosures about the people they interviewed.

And the disclosure should also include the methodology like, did they modify anything in order to actually dramatize it? Or did they disproportionately look at one part of it because they want to make the case for it?

Alayna: It’s really three parts: Disclose what you’re doing to the people you’re working with, the people you’re including, and then to the audience.

Subbu also talked about accountability. When a creator makes an unethical decision, they should correct the mistakes in their content and explain the corrections. Issuing an apology to those who were harmed is also important.

Morgen: Now before you get too invested and binge the entire podcast or documentary, try stepping away after the first 20 minutes or so, and reflect.

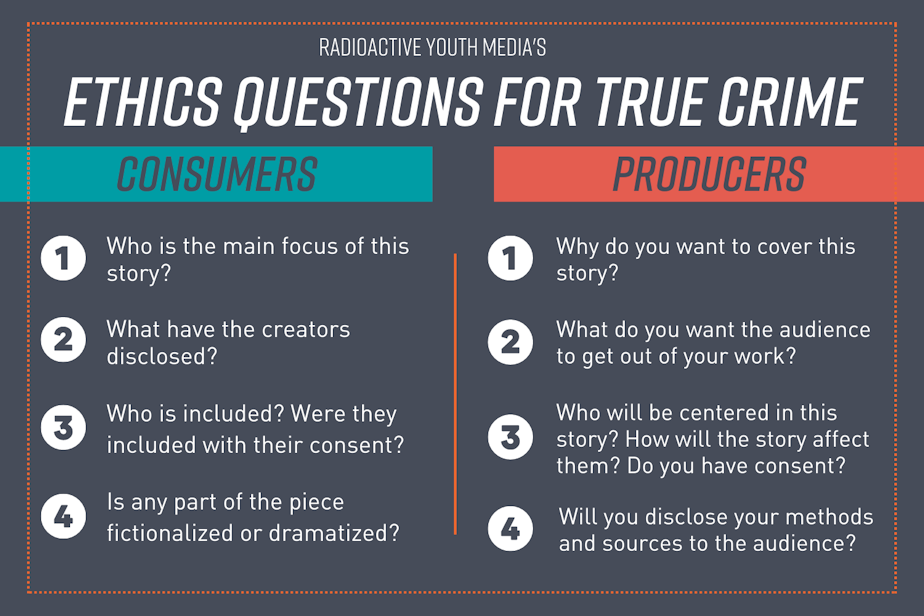

Here are some questions you can consider:

Alayna: Who is the main focus of the story? Is it the perpetrator, victim, related family members, or law enforcement?

Colin: What have the creators disclosed?

Alayna: Who was included? Were they included with their consent?

Colin: Was any part of the piece fictionalized or dramatized?

Morgen: These questions should push you to not only listen more carefully but to think about the implications of the piece.

And for current and aspiring creators of true crime, here are some questions for you to consider as well:

Alayna: Why do you want to cover the story?

Colin: What do you want the audience to get out of your work?

Alayna: Who do you want to center within your work? And how would that affect them?

Colin: Have you acquired consent from the people you included?

Alayna: Will you disclose your methods and sources to the audience?

Morgen: To any creators and consumers alike, remember: these stories are about tragedies that happened to real-life people. They aren’t characters that solely exist for your entertainment.

David Kushner, the host of "Alligator Candy," wanted to leave us with this:

David: Perhaps my advice would be, is to almost think of them as if they were in your own family, like to be that gentle about it. And aware.

This story was produced in RadioActive Youth Media's Advanced Producers Workshop for high school and college-age youth. Production assistance by Esmy Jimenez and Jadenne Radoc Cabahug. Prepared for the web by Kelsey Kupferer. Edited by Mary Heisey.

Special thanks to Karen Shackleford for providing background information, and to Blue Dot Sessions for the music.

Find RadioActive on Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube and Facebook, and on the RadioActive podcast.

Support for KUOW's RadioActive comes from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center and BECU.

If you have any feedback on this story, you can email RadioActive at radioactive@kuow.org, or click the teal feedback tab on the edge of this page. Reach out. We're listening.