Part 6: The Reckonin'

Native Americans once owned these lands, and they still treat the Columbia Basin as their sacred home. We’ve all benefited from that taken land, but now corporations are the West’s new settlers. Meanwhile, Cody faces a federal judge and his tight-knit rural community. His sons start taking over what remains of the family’s vast operation and beat-up reputation.

It started as an American success story. The Easterday family took a couple hundred acres of farmland in southeast Washington and grew it into a farming and ranching empire worth millions. Then, it all came crashing down.

Ghost Herd tells the story of Cody Easterday, the man at the center of one of the largest cattle swindles in U.S. history. Easterday invented a “ghost herd” of 265,000 cattle that only existed on paper … and swindled companies including an agriculture giant to the tune of $244 million dollars. Correspondent Anna King has spent two years following the fallout of the crime and its impact on a tight-knit rural community.

Ghost Herd is a story of family and fraud, but also a story about the value of dirt and the shifting powers in the American West.

Search for Ghost Herd in your podcast app.

Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network.

Sponsored

Episode 6: The Reckonin'

Transcript:

Anna King narration: I shouldn't be here.

In this restaurant, heavy drapes block the sun, so it looks like evening even during the day. I'm at Churchill's in Spokane. There are "lockers" rented by patrons for laid-down bottles of premium wine. The wait staff dress in evening wear and tuxes. And they fold your crisp white napkin again moments after you leave your seat.

Sponsored

Steak is what they do.

waiter: So to the cuts, the first steak on our dinner menu is the top sirloin.

Anna King narration: Our server brings over a huge tray of raw steaks wrapped in cellophane and gold foil to carefully explain each choice cut.

waiter: The rib eye and the cowboy rib steak the most intense marbling here, plus the rivers of fat running throughout, you could really swim in these steaks

Anna King narration: But I'm not really here for the steak. I'm here on a steak-out. Beneath this restaurant, down some stairs, is a dim-lit bar with low celings. The booths are upholstered in oxblood velvet. This is a place where deals get made.

Sponsored

And this particular night -- there's a group of lawyers from the Easterday bankruptcy ordering the most expensive options.

I am not here to discover some big secret. But after chasing the Easterday story for a solid two years, I just had to see this gathering in person. This whole fancy dinner is on Cody Easterday's dime, but he wasn't invited. These lawyers just closed the Easterday bankruptcy -- and earned themselves a nice paycheck north of 30 million dollars.

After my dinner, I steal off to the restroom. On my way, I peak inside the private room where the lawyers and guests are dining.

Right near the framed portrait of Winston Churchill, men in small groups stand around sipping wine. They're mostly dressed in dark suits.

It's hard to know what to make of this scene, but it feels like I am witnessing a changing of the guard. Family farmers are on their way out. Corporations are the new settlers.

Sponsored

In this final episode of Ghost Herd, we look at the myths we tell ourselves about the American dream and the West.

And, times up. Cody Easterday goes to trial. He faces the consequences of one of the largest cattle swindles in US history.

This is Ghost Herd. I'm Anna King.

The West has long been seen as a place of optimism, especially for the settlers that came here. A frontier where someone could make a name and fortune for themselves. That, 'Go west, young man' ideal. It still looms over us in our old movies ...

Western Movie: Man could make an awful nice little cattle ranch in that valley. You know, if you didn't mind being lonesome and had someone to kind of help him with the cooking and such.

Sponsored

Anna King narration: And it still lives with us today in fresh-cut songs, like this one from Jordan Davis:

song: said if you want my 2 cents on making a dollar count buy dirt

Anna King narration: but the ownership of farmland in the American west has never been static.

For example, Cody Easterday's father, Gale, got his start in ag at 17. Workin' 300 arces of ground.

The family was then able to build that into one of the largest farming and ranching operations in the Northwest. They had achieved the American dream.

But now we're seeing a major shift again. When Cody was forced to sell off that empire, it went to the highest bidder. To AgriNorthwest for $210 million dollars. And transactions like this are forcing us to examine the myths we tell our ourselves about who owns this land and who has power.

What three generations of the Easterdays were able to build, would be a lot more difficult if starting out today. Corporate competition, higher intrest rates, bank requirements, all mean hard work doesn't guarantee the success that the western myths of old have promised.

In a way, I've got a lot in common with the Easterdays.

When my father Gary, was a young man, he desperately wanted to farm. My mother was delirious and unable to protest with flu in bed when he did the deal. A widow was selling property. She wanted to move to town, since her husband had died. Dad went to see it. She told him it would be $2,000 down for all the acreage, and asked "What did he do for work?" Dad said he was in construction. She demanded, "Let me see your hands." Dad's hands were rough and callused and cut up from work. The nails chewed down. Satisfied he was a worker, the widow said OK. Dad sold his prized '56 Chev pickup, school-bus-yellow with the big chrome grill. He and mom scraped some more money up from family. And moved in to our place in the shadow of Mt. Rainier.

I grew up on that place, with Hereford and Angus cattle and horses. Fixin' fence. Running the wooded trails. Plunkin' hazelnuts into a rusty coffee can in summer -- these experiences on this piece of ground formed my rural heart. And that upbringing has defined my career.

Land deals like the one my dad made, aren't common now. And I'm privileged to grow up in a family that had something to sell, and the opportunity to buy that ground. In a way it's a classic Western tale.

These tales have shaped the American identity in many ways. But these old myths, the way our grandparents saw the West, can no longer sustain us.

Like the myth that if a person works hard, they could own a bit of the American Dream. Now, many farmers are just rentin' that dream.

Darrell Miles: And if you pull these apart, you can find the little kernels in here

Anna King narration: I am standing with Darrell Miles at the edge of his 9,000-acres wheat field and pasture. It's big, wide, rolling and open. The green heads of this wheat are in what's called the milk stage. That means the kernals are maturing and, if you pinch a kernel, there's a white liquid inside. His entire field is starting to go from green to gold, just weeks from harvest.

Anna: It's awful pretty.

Darrell Miles: Yeah, I wish it was thicker. No. It looks nice. I mean, it's, it's a fair stand and all of this rain we've got, it should be filling really nice.

Anna King narration: His place is called Juniper Dunes. It's a remote wheat ranch up here in Franklin County, a bit southeast of Basin City.

Darrell Miles: I like this area because it's, it's secluded. I mean, I, my closest neighbor is over three miles from me. I don't, I don't have anybody right out my door.

Anna King narration: But Darrell doesn't own this ranch. He rents.

Darrell Miles: growing up on a farm, but never owning a farm, I farm here because it's what I can get.

I don't own it I ha I have to basically take what I can I can I can get a lease on And so that's what put me here

Anna King narration: Many family farmers rent these days. Darrell's landlords live all over the country.

Darrell Miles: Um, I'm not sure that some of 'em have ever been here.

Anna King narration: In the Columbia Basin today, an acre of irrigated ground goes for about $20,000. And you have to have hundreds of acres of irrigated corn or potatoes or thousands of dryland crops like wheat just to make it. And even rents are getting high -- at $500 to $1,000 an acre for an annual rent depending on what that ground is raising.

Darrell says he's been a renter all his life. He wasn't handed any ground as a young man. Interest rates were too high to buy when he was young. Back in the 90s he had to have 40 percent down to even touch a place. And now, at 59 he could never work enough to pay back the sum.

But some farmers do own their land -- building on it for generations. Like the Easterdays. This gives them a leg up. They can be bigger, get economies of scale and gain more power from field to table.

Darrell Miles: if you've got land and you've got it paid for your financial situation's Much easier. So my neighbors that have farmed the same place that they inherited or bought way back, um, when we go through the bad years and we always go through the bad years, they're in a, in a better position to ride those years out

Anna King narration: That's the value of owning dirt. Having that equity gives you serious advantages you don't have as a renter. And as a land owner, you've got more security -- and you can take bigger risks.

Darrell Miles: Well, to throw out some old, old numbers. So the place that I used to farm sold for a million three in 98, the payment on it in round numbers was $90,000 a year. The year you pay that place off, you just got a $90,000 raise.

Anna King narration: Ninety thousand dollar raise. Pretty big deal when margins are tight. Even though Darrell doesn't have the advantages of owning land, he still takes a lot of pride in the work he does. But he sees a difference when corporations are involved. Darrel told me that when a coproration or hedge fund step in, what matters is the dollar.

Profits over place.

A close relationship to this valuable ground, to the landscape, is dwindling with absent land owners. People with no connection to the West.

And you can see that in the weeds, literally.

Marv Grassl: in the dry land country these noxious weeds are a problem and rye is considered an noxious weed in your wheat.

Anna King narration: This is Marv, Olivia Grassl's father. She and her husband Stacy Kniveton were the people with the potato problems I talked to earlier.

Marv's family moved here in 1951, the same year he was born. He's known this land his entire life. And he's obsessed with irradicating weeds from wheat fields. He's especially got it out for the rye.

Marv Grassl: And if you don't take care of it, it creates a major problem. You get deducted on your price.

Anna King narration: Marv's clothes are still dusty from working in the fields this morning. He was out pulling weeds just before we sat down to talk. His hands are stained from the soil.

Marv Grassl: Now, we've only got another few more days and it's too late.

Things have gone the seed. And that's why I gotta get out there and keep these, some of these noxious weeds from taking over. I can show you that a sea of rye it gets five, six feet tall. It will choke out kochia. It'll choke out a lot of the cheatgrass

Anna King narration: Marv can name hundreds of the weeds that are problems for farmers here.

Marv Grassl: scotch thistle, yellow star thistle, skeleton weed rush, skeleton weed.

Anna King narration: Dalmatian toadflax, you know, snapdragon

Marv Grassl: The tree of heaven? It's actually a tree of hell

Anna King narration: Marv tells me that some investor in Chicago or wherever has no clue about these weeds. They just trust that people like Marv will be around to manage it for them. He believes they have other priorities. He says investors and people who farm from afar extract resources from an area like miners.

Marv Grassl: What does a miner do? Take out the resources. And, uh, if they're not putting back into the ground or putting back into that crop, what they need to, to take care of it. you got problems and there's, that's the way it is in some of these places.

Anna: So you're saying these corporations kind of mine the area, it's like, they, they take the, they take all the money and they take the crop, but they're not, they're not putting back into the fair. They're not putting back into the churches or the schools or the communities.

Marv Grassl: I didn't say that. You said that.

Anna: No, I'm I, I can get it wrong. . You correct me. You correct me. Tell me what's right.

Marv Grassl: They're not that invested in the area because they don't have the, the history that they don't, they don't live here. I mean, you know, think about it. If you live in this area and you want your children and your grandchildren to stay with it, you're gonna invest in the area.

And that's what happened. That's why you want to have local people involved instead of people from. Wherever Washington, DC. Do they have a clue what's going on here? No.

Anna King narration: But Marv wonders what will happen when he's gone. He says this passion for weeds and caring for the land is something that you're born into.

Marv Grassl: And I try to teach it to my children, my son-in-laws and my grandchildren, that you gotta respect the land and take care of. it and it's an, it's a, it's a lot of work, hard work and a lot of time and money

Anna King narration: Long before corporations started moving in on this land, there was another dynamic shift in the power structure that ruled the West. Native Americans were here first. Now they own just a fraction of their original land, but many maintain a close relationship to all of that dirt.

Bobbie Connor: I think that farming and ranching families that have been here five and six generations have relationships like that as well. But for us, it's not like one place is as good as another place.

Anna King narration: I drive down I-84 to Bobbie Conner's place outside Pendleton, Oregon, to see this relationship first hand.

Bobbie Connor: It's all of the places together that are that landscape of memory. That embraces us and enfolds us and enriches us. And I just can't imagine life without that. It's hard.

Anna King narration: Up on top of Cabbage Hill ... I meet Bobbie. She's with her horses.

Bobbie Connor: wanna close the gate, Anna? Sure. Just hold the gate for us for a second.

Anna King narration: On a late summer's evening, Bobbie Conner with her brother Brian, grooms one of her horses named Tennessee. He's a 28-year gelding captured in the BLM desert near Burns. She runs a metal curry comb over his haunches.

Bobbie Connor: Grass seed and stickers will travel up into the tail and just annoy the heck out of him

Anna King narration: She uses her fingernails to pinch weed seeds out from the base of his tangled tail.

Bobbie Connor: he could have rubbed his whole tail off if he was really in bad shape. But clearly he hasn't done that.

Anna King narration: The sun is going down across the Umatilla Basin and the Columbia Plateau. Tennessee shifts his feet.

Bobbie is the head of the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute. The only museum along the Oregon Trail that tells the story of western expansion from a tribal point of view.

Bobbie bought this land partly because it's an elk nursery. It's where mother elk come to have their calves each year. She tells me that her sense of ownership is an accountability to the land. That's something that she learned from her mother, grandmother and uncle.

Bobbie Connor: So my cousins who grew up in Idaho had the places where they got medicine. They had the places where they got their meat. They had the places where they got their fish and so we all have relationships with place.

Anna King narration: For Native Americans like Bobbie -- land, food, water and people are all in relationship with each other.

The salmon that swim up the Columbia are brothers, and the roots they dig are sisters. They are relatives, coming back to feed the people.

Bobbie -- of the Umatilla reservation in Oregon -- says the table is a metephor for the universe that is native culture.

Bobbie Connor: So the foods on the table, when they're set at feast, you know, water is the first thing we take and the last thing we take a sip of, but a taste of the salmon, a taste of the various fishes,

Anna King narration: During these religious ceremonies foods are tasted by the people one by one as leaders call their names: čúuš! (Choosh) For the water. And núsux (new-sux) for the salmon. And nuukt (nuukt --like looked) for the meat. Khoush (COW-sh) , for the one of the types of roots. And wiwnu (wooh-new) for the berries.

Bobbie Connor: All done as a sacrament to remember the law that sustains our people, which is that if they take care of us, they have to take care of them in their home. That's a covenant we have with everything else that lives here and a covenant with the creator that gave us this fabulous place to live.

Anna King narration: When we get back, Cody goes to trial.

Break

Anna King narration: The growth of the Easterday farm and ranch is one story of Western expansion. Cody created 265,000 fake cattle, a ghost herd. His swindle speaks to the drive to be bigger, produce more. Grow, build -- get more for yourself.

But he could only live that for so long. He got caught. And Cody was forced to sell off much of his empire to pay those debts. And he plead guilty to his crimes.

The community has been waiting two years for him to be sentenced. Wondering how much time, if any, he will serve for his crimes.

And now he's about to stand before the federal judge.

And Cody's actions have forever changed the reputation of the Easterday empire:

Darrell Miles: I mean, he broke the law and I don't care who you are. If you break the law, you should do time

Alan Schreiber: I don't, I don't feel sorry for Cody. I feel sorry for the people around him, they are gonna have to deal. with The sins of the father.

Nicole Berg: just the publicity for agriculture and the trust in the public eye. That was the part that's very unfortunate,

Darrell Miles: A lot of those people lost their jobs. And those weren't high paying jobs. So he hurt a lot of people with his actions.

Alan Schreiber: Easterdays was a brand name. And it's unfortunate that this had to happen to them. And I think they would like to reclaim their good name.

Anna King narration: I'm standing outside the courtroom where Cody Easterday will recieve his sentence. I'm in this hall with about 60 people who aren't fans of my reporting on Cody. My hands sweat. I'm feeling sick in my stomach. But it's nearly the atmosphere of a wedding in the hall. Women sporting heels and beachy wave hair are grouped in tight bunches. Some have purses with long-tan-leather fringe. Men in dress shirts and suits shift their weight back and forth, others in boots and straw hats lean up againt walls waiting expectantly eyeing the crowd. And neighbors slap hands, as each newcomer enters.

Everyone files in to the courtroom and Cody takes a seat at the large table on the left facing the judge, his back to his wife and children seated in the front row. There's no recording or cell phones allowed.

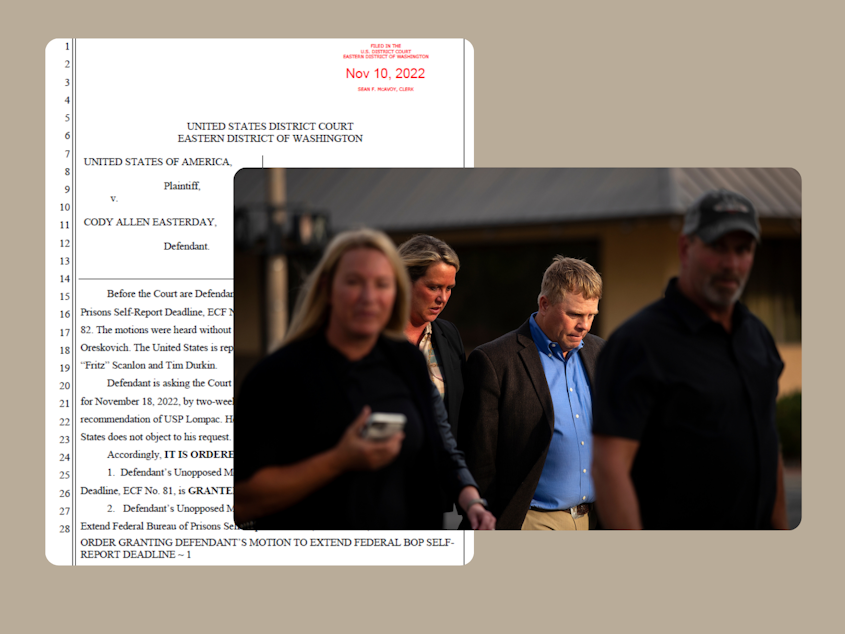

Cody's face is ruddy from decades of the Columbia Basin's beating sun. His forehead blank white like a sheet of crisp paper from always being protected under his hat. He wears a blue dress shirt, and dark sports coat with khaki pants. On his silver belt buckle rides the family's steerhead punched there in gold.

This is Cody's sentencing hearing, lawyers will argue to the federal judge how many years Cody will get.

The prosecution goes first with it's argument. The lawyer says Cody's case is, "massive, brazen, and long term." The prosecution says Cody lied to those who had the misfortune of trusting him as a business partner. The lawyer agrues this is a seroious crime and Cody deserves a serious pentalty, asking for a sentence of 10 to 12 years.

Cody's defense lays out the story of a life-long farmer with deep ties to his community.

The defense also emphasizes Cody's inability to dig himself out of his gambling addiction on the futures market. He became secretive and distant with his family. "He lost and lost and lost."

Finally, it's Cody's turn to speak: "Thank you your honor. I'm sorry to all the people who have supported me through this whole thing ... I'm sorry, this is not the man I am."

The court takes a 10 minute recess, the crowd speaks in low voices. Some of the buoyancy of before is gone. And then -- the judge comes back in to give his ruling.

The federal judge explains how he has had to hand down sentences for crimes related to crystal meth, fentanyl and other addictions. He says: "I don't see the difference here."

The judge says: "This empire you built, you've destroyed."

Cody's boys shift in their seats. Bending low elbows to knees. Debby, Cody's wife pat pats one son's broad back. A man, but still a child.

Then the judge hands down the sentence ... 132 months -- that's 11 years.

If the mood was expectant like a matrimony on the way in, then coming out -- it is a funeral. People look grim, shocked and walk quickly for the doors single file.

Cody, walks right passed me. Head down, he doesn't look in my direction. Some women cry. Then, they turn to go. They still have a long drive ahead, back to Basin City.

I've stuck this ride of a story for two years. Since this news broke, Cody hasn't talked to me. And, I do have empathy for him and his family. They'll be forever changed.

Now, the next generation of Easterdays must carry on the family's legacy without the help of their father.

Cody's daughter Kody Dee is about 27. The young men Cole, Clay and Cutter are about 25, 23 and 21. The three sons have started a new farm.

They've had to move their operations from their vast river farm, to further-away parcels north and south. Walla Walla to upper Franklin County. They've been pushed to the margins of the Columbia Basin.

The sons' maroon semi trucks haul loads of onions and potatoes on highways near where their grandfather Gale died in that terrible crash.

On the truck doors, the old vinyls that once said "Easterday Farms," have been peeled off. Now, the new company name of the young men "Triple E Farms" replaces it. But some things remain. Like the steer head family brand emblazoned in silver riding shotgun on the door. The brand, seared into this family's history and hide, rides on.

When you're a farmer, the land becomes a part of you. You breathe it. You eat it. It's under your nails. You even eat a bug now and again. It's in you.

And reputation too, is a part of you. There's a weight to it. It plays a part in what you can and can't do in life. And the Easterday's reputation has taken a major hit. Farm families work the same ground for generations. So, these boys can't run from their name. They can't start over. Just time on it, will crust over the hurt. The damage. The reputation.

Northwest tribes move through life welcoming the seasons. First comes the wild celery, then the salmon, later the berries. It's a wheel that turns over each year. There is a light within the foods that they eat. They believe what they do to the earth, they do to themselves. Bobbie Conner says the way we're living now, doesn't feel sustainable. Maybe the way the Easterdays' were farming wasn't sustainable either.

I wonder if they'll be able to repair the family reputation, build back in the coming generations. Or if the Easterdays will collapse inward without their strong patriarchs-- like a furrow in the earth with too much rain all at once.

Late last year, Cody's got in his pickup, maybe with his wife, and drove in and reported for prison.

I imagine he drove past icy irrigation pivots. Hovering just above snowy potato fields like dino-sized steel dragonflies.

A bleak, grim winter. Farmland asleep.

Perhaps Cody would have noticed something small going wrong in a field, something out of place -- but have no time to fix it. A farm kid, now 51. With no free time left. A ghost no longer visible on this vast, bitter landscape, he'll keep driving toward the reckonin'.

And when spring arrives, Cody's children will have to figure the plantin' without him. Now quickly grown, they'll try to step in and plow out their father's mistakes.

This is Ghost Herd. I'm Anna King.

Credits

Anna King narration: Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network, a coalition of public media podcast makers. To support our work, contribute to KUOW, NWPB or your local NPR station … and tell a friend or two about this podcast. It helps.

Ghost Herd is produced by Matt Martin, and me, Anna King. Whitney Henry-Lester is our project manager.

Jim Gates is our editor.

Fact Checking by Lauren Vespoli

Cultural edit by Jiselle Halfmoon

Our logo artwork is designed by Heather Willoughby.

Original music written and performed by James Dean Kindle

Recorded by Addison Schulberg

With additional musicians Roger Conley, Andy Steel and Adam Lange

I'm your host Anna King.

If you have thoughts or questions about Ghost Herd, we’re listening. Get in touch at KUOW.org/feedback